Find shallow flats near deep edges. Search rivers feeding Merrymeeting Bay, also the flats of the bay itself, because that’s the only place carp live here in Maine, introduced by Europeans as a food source in the late 1800s. Even though they’ve been here for around 150 years, they’re invasive, like most of us, if you go back far enough.

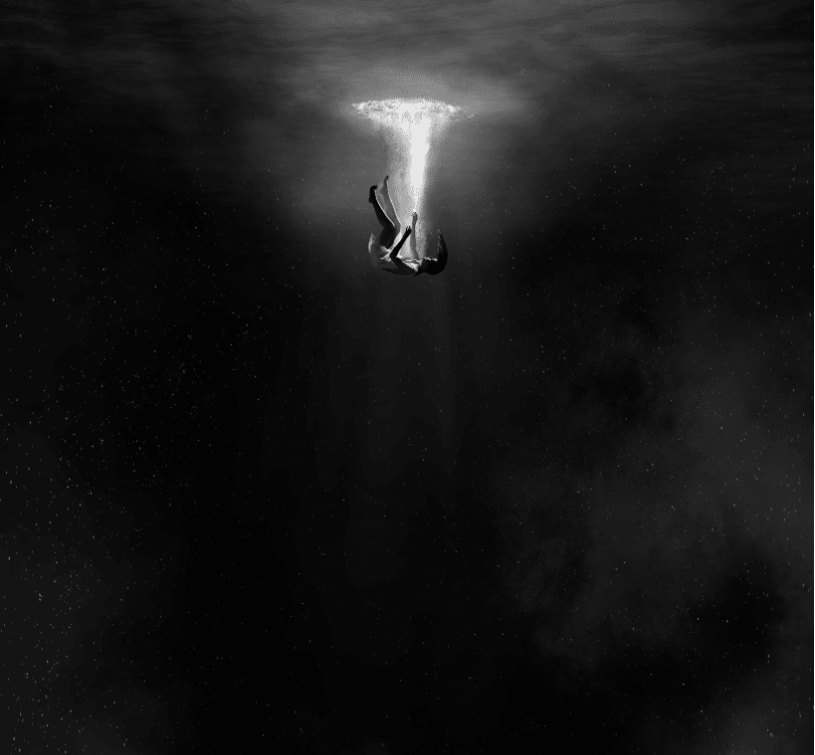

Do: watch them and learn. Watch the floating carp sink and tip down, watch the mud cloud rise around it, the carp vanishing, disappearing somehow. Look for mud clouds. Not the quick-dissolving plumes of spooked fish (you’ll see those too) but the slow, ash-cloud-rise that betrays the feeding carp, bulldozing for mollusks and worms.

Look for tails. Not the full-on outline but the not-quite-right color — bronze with pink hues, then the slow, queen-wave motion of a feeding carp tail.

Don’t: cast at floating fish. Don’t even bother. It’s tempting — their O-ring mouths just beneath the surface, their porky, bowling-pin bodies. They look dopey, easy to fool, but don’t kid yourself.

Don’t cast at fast-swimming fish either; they won’t eat your fly. Don’t cast at the lead fish in a string; spook it, and the rest will veer off too, like geese. Don’t take too many false casts (they’ll sense you), don’t rock the boat (they’ll sense it), don’t cast atop their heads or swim your fly toward them (prey swims away from predators, a wise guide once told me).

Do: wade whenever possible. You’ll make less noise and spook less fish. Wear waders (or get duck itch, as I did recently). Do: keep carp spots close. Where else can you sight-cast 15-pound tailing freshwater fish in 12 inches of water?

Do: cast at slow-sliding fish, the ones exiting mud plumes. Don’t: strip your fly too fast (or at all).

With rod high, drag your fly then drop it naturally near the carp’s eyeball, fly going away from fish. Watch body language. Quick flare or turn equals spooked fish. Slow turn plus tip-down means get ready.

And whatever you do, after all those fishless days (there will be fishless days), all those refusals (embrace them), don’t wait to feel a strike. You’ll feel nothing.

Do: watch for the slightest quiver, the head buried atop your fly, the enthusiastic tail kick. This can’t be taught: it’s intuition, fishy-ness, a sixth sense. Feel nothing. Strip long and get tight.

Do: add backing to your fly line before the trip. The big ones (over 10 pounds) will empty your fly line. Check your drag. Check your hook point. Let them run after hookset; they’ll bend the hook if you don’t (my friend Courtney can attest to this).

Fight them quickly. They’ll tire after a few good runs. Anticipate the surge when they first see you, or when they first see the boat. Bring a big net, or, if you forget one, grab the thick meaty band near the tail. Get ready for a thrashing.

Remove the fly gently from the rubbery golden mouth. Take a few photos. Admire its awkward beauty: large prismatic scales, drooping barbells, powerful paddle tail. Revive the carp slowly, so it kicks off under its own power, back into the murk. Do tell your trusted friends, but not the ones that would give away your spot.

Go home and tie carp flies. Experiment with color and shape and sink rate. Fall asleep thinking of mud plumes and wagging tails, the strip-set and the whining drag. Wake up and check the tide charts; plan your next day of carp hunting.