There are many factories around the world, but few look anything like semiconductor fabs.

These places – fabrication plants, to give them their full name – are otherworldly in all sorts of respects.

Bathed in yellow light and populated by workers wearing head-to-toe white suits, visiting one of them feels like entering the world depicted by Stanley Kubrick in 2001: A Space Odyssey.

Up until recently, few were aware that the UK hosts one of these spaceship-style plants as well – yet the Newport Wafer Fab (NWF) has for decades been a quietly important part of this constellation of critical locations, producing the tiny silicon chips that help make the modern world go round.

But in recent months, after Nexperia – a Netherlands-headquartered firm with Chinese owners – agreed a deal to take over NWF, this place has suddenly found itself thrust into the limelight.

The latest of these headlines has concerned a decision by Business Secretary Kwasi Kwarteng to review the deal, which went through last year, on national security grounds.

The original deadline for his decision was last week, but – as Boris Johnson’s government imploded – the Department for Business Energy and Industrial Strategy asked for a 45-day deadline to make its decision.

So the fate of the plant, which sits in a campus just outside the South Wales city of Newport, hangs in the balance, even as the Tory Party wrestles its way towards a new leader.

And as often happens when stories like this hit the front pages and everyone is exceedingly busy doing other stuff, much of the nuance and detail has been lost along the way.

Some claim the plant would be bankrupt without the Chinese; some say it is so small and piddling compared to silicon giants like Intel or Taiwanese group TSMC that we really shouldn’t be making so much fuss about it; others say the chips being made there are so important for national security that its sale would compromise Britain’s military; some have claimed that Nexperia would shut it down after the purchase has been approved.

Yet of course the truth is far more nuanced than this, which is to say, far more interesting.

And in this case there is an added twist, which is that most people in government aren’t entirely aware of what this plant actually makes.

So perhaps the best place to begin is with a brief primer about what semiconductors actually are.

What are semiconductors?

We tend these days to think of silicon chips as the brains of computers and smartphones, for good reason: because this is the most prominent type of semiconductor.

Yet in fact that type of silicon chip – important, sexy and valuable as they are – is only one sub-sector of an extraordinarily wide range of chips.

After all, what semiconductors ultimately are is a type of switch.

These chips that represent the brain of your smartphone or laptop are really just a dizzying number of switches (transistors to call them by their technical name) used for computing tasks, with so many of these binary on-off switches that you can array them into something that can be programmed.

These types of logic chips are truly a thing of wonder, and it’s true that this field is these days utterly dominated by TSMC and Intel.

What they do is true nanotechnology, with transistors that can be measured in mere nanometres, with smaller dimensions than can be seen in visible light.

But this is not the only type of semiconductor. For there is another field of this industry which deals not with computing, but with power.

These semiconductors are not thinking devices; they really are just switches.

They can be activated to transfer power from one place to another.

You might not be especially aware of the existence of these semiconductors, but they are quite literally everywhere.

They are the things that kick into action when you turn on your hairdryer or hoover.

When you push your brake pedal in your car or wind down your electric window, what is happening in practice is one of these semiconductors being triggered and sending electrical currents down a wire.

Any electrical device you have which will have at least one (and probably many more) of these power semiconductors in there.

Were you to open up the power cable you use to charge your phone, you will find one or two tiny chips inside it, and the chances are they may have been made by companies like Nexperia and Newport Wafer Fab – for this is their field.

The reason it’s worth internalising all of this is because once you realise what they’re making in Newport is very different to those “brain” chips they make in Taiwan, it throws a whole new light on this saga.

They might be made largely of the same silicon, but the skill and techniques used by these different wings of the semiconductor sector are really quite different.

Comparing what they do in Newport with what they do at TSMC’s fabs in Taiwan – as much of the coverage of this factory has done – is like comparing apples and pears.

Actually, within this sector, where chips are broadly speaking simpler but (and this is important) more robust and capable of dealing with high flows of power than their “brain” counterparts, Newport is a surprisingly big deal.

You get a sense of this when you visit, as I did recently.

This is what’s known as a “ballroom” fab, in which the floor where the chips are made sits directly on top of a complicated basement level – the sub-fab – where pipe upon pipe of gases are fed up into the machinery etching patterns on to silicon.

The foundations here are driven down into the bedrock far beneath our feet, in order to ensure there are no vibrations at all.

Because even the smallest vibration could cause a chip to be damaged – so small and precise are the movements of the lithography machines on the floor above.

Why is the Newport factory so valuable?

That brings us back to the key thing you need to know about these places.

One of the most important marks of a good chipmaker is not merely the clever IP they have in-house, but their ability to make working chips consistently.

That might sound like a statement of the bleeding obvious, but it really matters.

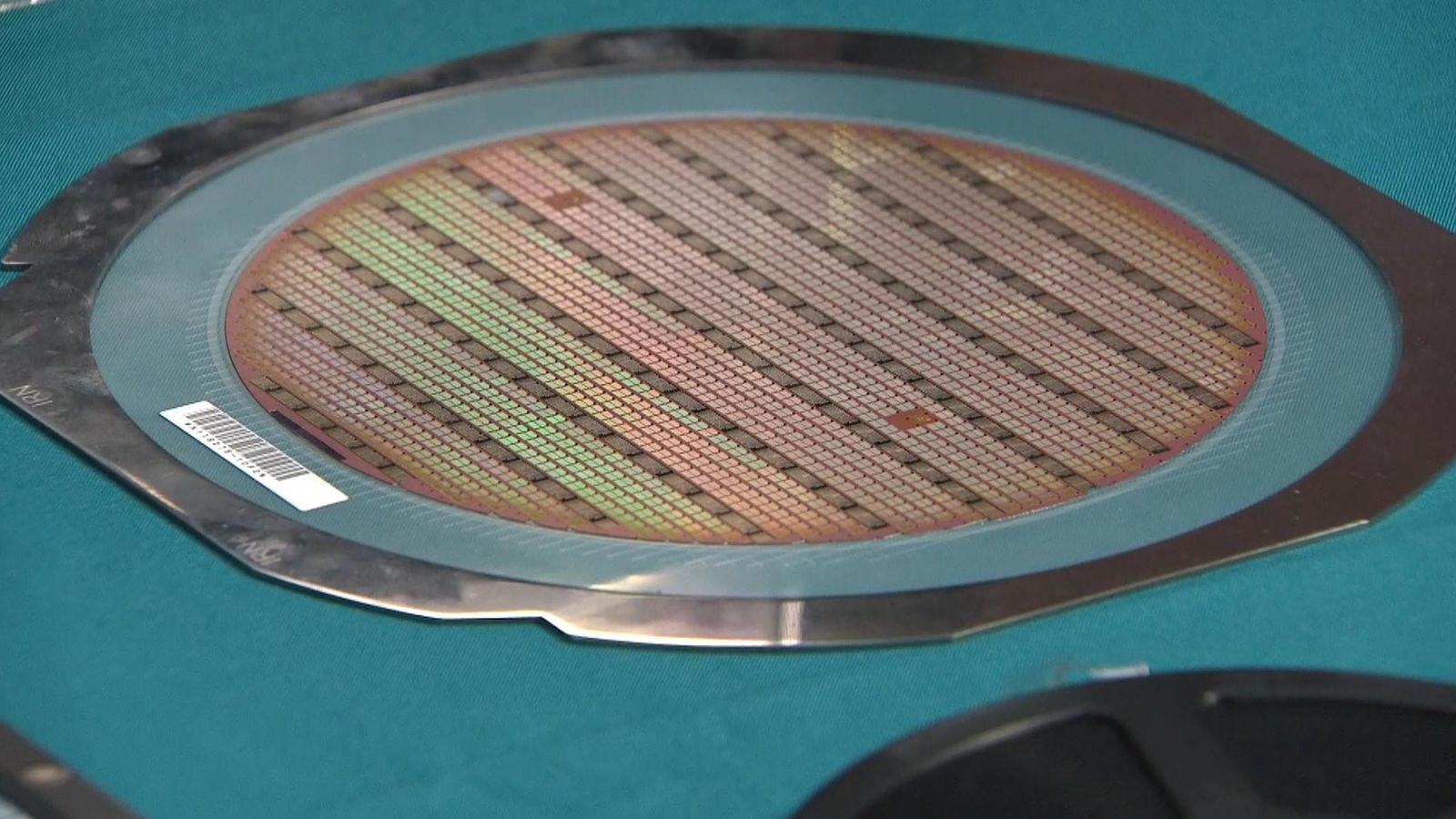

All silicon chips begin their lives as a large circular slice of pure metallic silicon – a “wafer”.

These wafers are expensive, and even more expensive are the machines in which they sit and whizz around – a process which takes months – as the transistors are etched into them.

Eventually, at the end of the process here in Newport, the wafers are imprinted with many hundreds of little squares, each of which will be sliced off the wafer and will later become a silicon chip.

But these wafers rarely yield chips that all work; sometimes a fleck of stray dust will land in the wrong place, maybe there was an unexpected vibration or some light damage (hence why the fab is bathed in yellow light that is less likely to affect the silicon).

At least a few chips on each wafer are unlikely to pass quality control.

So, a mark of a fab’s success is its average yield, and it turns out on this front Newport is very good indeed.

With a yield percentage in the very high 90s, among power silicon chipmakers it’s one of the best in the world.

The other thing that’s under-appreciated is how valuable this site is.

If you wanted to tear down this building and reconstruct it, with all the machinery, it would probably set you back about a billion pounds.

It is, in other words, one of the most expensive factories in the UK.

Now, it’s certainly true that what they do here is categorised as the low-value, high-yield end of the semiconductor sector.

In a typical car these days you might have hundreds of these power chips for everything from brake lights to wing mirrors, but only a few of the logic chips – those “brains” – to work the navigation and media console.

If you want a sign of how much these semiconductors matter, recall that a sudden shortage of them – both the “brain” ones but also the power ones – has caused a major downturn in car manufacturing, not to mention other sectors.

Without even these small power chips, you can’t make, well, pretty much anything.

And while it’s true the fab in Newport is nothing like the multibillion dollar fabs you find in Taiwan, it’s not really supposed to be. It’s serving an entirely different market.

Moreover, while for most of its existence power silicon has never been an especially sexy field, that is starting to change, in large part because of the rise of electric cars.

In battery-powered vehicles, where range is everything, even a small improvement in efficiency in the power silicon inside your inverters can help increase a car’s range by tens of miles.

At the cutting edge, some firms – including Tesla – are beginning to employ new so-called compound semiconductors, which use chemicals such as gallium arsenide and silicon nitride in place of traditional silicon, to create even better-performing power semiconductors.

And in recent years, Newport has been at the centre of a compound semiconductor cluster here in South Wales.

Nor is this the only exciting thing going on in this obscure corner of the silicon world.

There is also what is known as “silicon photonics”, whereby you can use a combination of light and electrical signals to do new things, among them creating medical sensors.

Imagine your smartwatch could easily sense your blood sugar levels, your blood pressure, your core body temperature – all things which are currently beyond the capability of most devices.

Photonics promises to deliver precisely these functions, while also holding out the promise of creating chips with many times more computing power than today’s silicon.

How have UK companies been affected by the sale?

One company at the forefront of this is a British firm, Rockley Photonics.

They were planning to use Newport, alongside an American fab, to make their sensors which could go into those next-generation smartwatches.

In other words, these crucial sensors in cutting-edge devices could have been made in Wales.

However, since the Nexperia takeover, Rockley is going to have to shift all its production overseas.

There is a logic to this: before Nexperia took over, NWF was what’s known in the trade as a “foundry” – a fab which could be contracted to make chips for any designer.

Now it’s owned by Nexperia, it is going to be making chips solely for its parent company.

This, says Rockley’s founder and chief executive Andrew Rickman, is a disappointment.

“We obviously had to move on,” he says. “And in the future as we look for additional capacity, if it was available to us to manufacture in the UK, that would be wonderful.

“As you analyse the UK, we have this incredible set of expertise around compound semiconductors, and a whole range of different process technologies associated with it, which do new and wonderful things. These are markets that are expanding very rapidly.

“So compared with traditional semiconductors, where perhaps the US or other parts of Europe are better places to build additional capacity and factories, in the UK, we’ve got this opportunity to actually own this particular area of compound semiconductors.”

This is the main objection among industry insiders to the takeover: it effectively means Newport goes from being a potential pioneer to being a workhorse.

But even here the story is not so simple.

Will the plant help China win the race to dominate power silicon production?

When I visited Newport, I was ushered into the wing of the plant which was supposedly the thriving seedbed for all this compound semiconductor innovation.

It turned out to be an empty cavernous space filled with old, retired machines and a few pieces of gym equipment.

If this was supposed to be the future, it didn’t look much like it.

It is hard to know how to balance these claims: outsiders saying Newport was a world leader in this new, exciting field; insiders saying it was nothing of the sort.

What isn’t in doubt is that Newport was and is a strong player in the world of power silicon.

Though that raises further questions: is that strength something being targeted by Nexperia’s Chinese owners?

The question is of more than trivial importance, since we are in the midst of what many have described as a new Cold War, with semiconductors one of the fields in which the blocs are competing.

Chinese firms are investing many billions of dollars in semiconductor manufacturing, but this turns out to be a far trickier field to excel in than, say, steel manufacturing.

However, remember again that there is no single unified semiconductor sector: there are many.

And while China is certainly struggling to compete with TSMC, and for that matter Intel, in producing single-figure nanometre resolution logic chips, it has a better chance of winning the race to dominate power silicon production.

Might Newport be a part of this story?

:: Listen and subscribe to The Ian King Business Podcast here.

Malcolm Penn, chief executive of Future Horizons and one of the most respected experts in semiconductors, certainly suspects so.

“[Newport has] a lot of advanced processing techniques, which many of their competitors can’t do,” he says.

“Nexperia couldn’t do it – and that was one of the motivations for [buying] Newport Wafer Fab, because Nexperia, with its own capability, couldn’t do some of the things they wanted to do.

“So they went to Newport Wafer Fab initially as a customer.

“And then they then acquired it. So now they have ownership of that as well as just simply being a customer for this technology that they needed, that they didn’t have in house.

“And that know-how is likely to be transferred to Nexperia’s factories in China.

“Their parent – a company called Wingtech – is building a brand new, large facility in Shanghai, and they need the techniques – the IP in Wales – to transfer over to China to bring that factory up-and-running.

“Otherwise, they’ll be delayed at least a year, if they had to develop that in house. So it really is a shortcut to bringing that factory up to speed.”

Does the UK need its own silicon manufacturing capacity?

This brings us back to the latest chapter in this story – the business secretary’s national security investigation into Nexperia’s takeover.

Would it cover issues like the above? Perhaps, perhaps not.

Anyway, it’s not entirely clear that we’ll get a decision from this business secretary.

The new deadline for the decision is now in the second week of September, by which time we should have a new government.

How much time they devote to decisions like this is unclear, given how much else is on their plates in both political and economic terms.

But it’s also pretty clear that the story here is not just about national security.

It’s about a broader question: how important is it that Britain has its own silicon manufacturing capacity? Actually, the question is even more basic than that: what is Britain’s semiconductor strategy? And here, for once, there is a clear answer: we do not have one.

Most other major trade blocs, including the US and Europe, have whole committees and teams devoted to semiconductor strategy, for obvious reason: without these chips – both the complex ones with the brains and the simpler ones made here in Newport – we are in big trouble.

They constitute the nervous system of global infrastructure – so it makes sense to think long and hard about one’s part in that business.

Yet the UK has no established strategy. Indeed, it isn’t even especially clear who in government is in control of the said non-existent strategy.

For the past year or so officials at – bizarre as this may sound – the Department for Culture Media and Sport have been charged with putting together a semiconductor strategy.

The exercise has proceeded at a snail’s pace and it is not clear it will ever conclude.

Yet the business secretary’s intervention makes it clear that he and his department believe they should be in control of government policy here.

Where Downing Street falls or rather fell in this is anyone’s guess.

Former Johnson advisor Dominic Cummings has long opined on the importance of these important technologies – yet it’s not clear anyone in Whitehall is aware of precisely what happens in Newport, precisely how it fits into the global semiconductor industry, and the risks and opportunities associated with the Nexperia takeover.

Having read this far, the chances are you already know more than most of them.

Most people in government are not aware we have a thriving, if small, group of companies focused both on the design and hardware of computer chips.

They might have heard of Arm, the extraordinary British-born company whose designs are now embedded in most modern chips, but that’s about where it ends.

So perhaps at the very least this episode could serve as a reminder about what this sector actually does.

What will happen next?

The question of what to do next is still hanging in the air.

Since the takeover seems to concern the grey area between national security and industrial strategy, no one either in Whitehall or Newport feels confident about the decision that will be taken. What reigns right now is insecurity.

This is proving testing for the workers at Newport.

Employee after employee told me that the company had faced continuous financial struggles before the Nexperia takeover.

These had come to a head in the recent semiconductor shortage when the company had, paradoxically perhaps, struggled in the face both of a rise in demand but also in the cost of its raw materials.

Read more:

Chinese tech deal blocked on national security grounds

Britain’s best-kept industrial secret that could save the planet

After this financial rollercoaster, finally, in the past year, they had had pay rises and the fab had had some meaningful investment, with new machinery installed.

At last, the site seemed to have an opportunity for stability.

Yet with the decision still pending, everything is in limbo all over again.

The Newport site is festooned with Nexperia signs and there are Chinese workers to be seen around the site.

Yet no one knows if this relationship will be short-lived – or what will happen next.

And with the Tory leadership battle consuming all the attention in Westminster, little time or thought is being given to this place.

Toni Versluijs, the UK country manager for Nexperia, said: “We are looking for a swift decision. Usually uncertainty or changes in leadership don’t facilitate fast decision-making.

“I think Nexperia brought stability and certainty and a clear outlook for the people [here]. And the investigation has basically put the clock back a bit.”