Lukcia Sullivan ran her hand across her scalp as Dr. Jeffrey Spiegel checked the IV line in her other arm and asked her about any allergies. It was a routine morning for the surgeon. But it was momentous for Lukcia, 69, who had been waiting for this day for decades, ever since she knew she was a girl.

In a few moments, she would be wheeled into the operating room of a clinic in Newton, Massachusetts. There, Spiegel and his team would spend the next six hours resculpting Lukcia’s skull and facial tissues so she would appear more feminine. The procedure would involve narrowing her jaw, brow bone and chin; augmenting her lips; and reconstructing her nose.

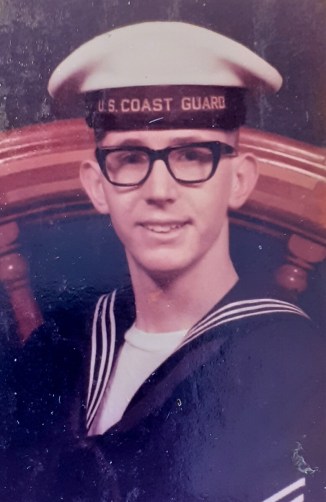

Lukcia was assigned male at birth and presented as a man for the first 67 years of her life. Her sensitive nature made her a target of ridicule, however, first as a boy growing up in a rigidly traditional Irish-Catholic family, and later as a service member in the Coast Guard and U.S. Army. So she suppressed the mannerisms that others deemed too feminine and muted her true self to adapt to her gendered environs.

When she retired in 2018, she took stock of her life. She wanted to finally look like the woman she knew she was. Her surgery last December represented part of her transformation. Another step has involved reintroducing herself to her family and her community.

The Bangor Daily News followed Lukcia for a year as she underwent a series of surgeries to align her body with her gender identity after she began presenting as a woman in October 2020.

Lukcia wanted to show the world the realities and challenges of transitioning at an advanced age, even in a state like Maine that has some of the strongest available legal protections for LGBTQ residents. She wanted to send a message to younger people that they do not have to live their lives as someone they’re not.

“There are other young men who don’t need to live the lifestyle I did,” she said.

What’s more, sharing her story publicly would help her erase her previous life and any doubt people might have that Lukcia is a woman.

“I wanted to come out loud and proud,” she said. “I didn’t want people to whisper, ‘Is there something going on with him?’”

For Lukcia, her journey is not complete without sharing it. It is important to her, regardless of what others think, that they at least know who she is. She has known for many years. Now comes the telling.

“The fact I subjected myself to so much intimate dialogue and detailed photography makes it real. [My identity] is not going to be able to be dismissed as easily, because it has depth and fabric,” Lukcia said.

‘Heading to see the wizard’

Pure grit and gratitude have shaped that fabric of her identity. Lukcia began hormone replacement therapy in November 2020, taking medication to help her body produce estrogen and suppress testosterone production. She grew breasts. Her skin softened. She cried more easily.

She officially changed her name last summer to Lukcia Patricia Sullivan, choosing a first name that honored Luke, the name she received at her first Holy Communion. She came home from the Bureau of Motor Vehicles after changing her name on her driver’s license and cried for two hours.

Clockwise from top left: Lukcia Sullivan walks up her driveway to get the newspaper to read with her morning coffee on Dec. 8, 2021, days before her first of two facial feminization surgeries; Lukcia reads alone at the dining room table while drinking her morning coffee; Lukcia sits on the bathroom counter to be closer to the mirror while putting on makeup; Lukcia looks through the clothes hanging in her closet that reflect the girl she had known herself to be since the age of 4; Lukcia applies makeup most mornings, for which she is still learning techniques. Credit: Linda Coan O’Kresik / BDN

She adopted a uniform of elegant blouses, skirts and dresses, opting almost exclusively for soft pinks.

But it was while sitting in the surgical suite with Spiegel that it registered for Lukcia that her journey toward presenting as her true self had reached a critical point. She would undergo another facial feminization surgery with Spiegel two months later, then fly to Pennsylvania in May. There, she would receive a vaginoplasty from Dr. Christine McGinn, one of the world’s top surgeons who specializes in transgender health care and who is also a transgender woman.

“I already knew I wasn’t going back,” Lukcia said. “That first surgery was the first step on the yellow brick road. I was heading to see the wizard.”

That December morning, she forewent her usual silky blond wig. She arrived at the nondescript, monochrome clinic at 6 a.m. and donned a surgical gown. As she sat in a chair under harsh fluorescent lighting before the procedure began, she peppered Spiegel with questions about complications like swelling.

“Every woman has difficulty looking feminine,” Spiegel reassured her. “They worry about aging, their facial structure, their skin quality. Don’t worry. I’ve done this over a thousand times.”

An assistant fitted a mask over her face, and she immediately dropped off to sleep. Spiegel and his team got to work.

‘Girls did certain things, boys did certain things’

Lukcia’s story began as the middle child of seven boys and girls in a family that not only rejected the idea that someone could be transgender but actively punished Lukcia for playing in ways her father thought was too feminine. She grew up in rural Harwinton, Connecticut, and gravitated toward female friends in her early adolescence. She was more interested in embroidery and cooking with her mother than anything her brothers did.

Her father tried vigorously to stamp that out and force her into more stereotypically male activities. He hit Lukcia every time he caught her dressing up in her sisters’ clothes or playing house with other little girls. One of the last times they saw each other, in 1978, Lukcia’s father threatened to kill her because he didn’t want a “gay son,” she said.

“In our family, things were very structured and regimented by sex,” said Debbie Seymour, 68, Lukcia’s sister. “Girls did certain things, the boys did certain things. My father really, truly believed that vacuuming would ruin a boy.”

Transgender people have a different gender identity and expression than the one they were assigned at birth. Some transgender people, though not all, are diagnosed with gender dysphoria, a clinical set of criteria that refer to the persistent distress a person feels when their assigned sex doesn’t match their gender identity.

Lukcia coped with that distress by tending to her family’s farm animals, and she left her parents’ home at 15 to live with other families while she attended an alternative high school for vocational agriculture. But she didn’t escape the influence of her father, who forced her into the Coast Guard at 17 after a fight.

Her three years there led to more military service: She joined the Army to pay for college and graduate school in Florida to become a veterinarian. After graduating, she served in Bosnia, Germany and Iraq as an officer training dogs to sniff out bombs and landmines. She left active duty in 1994 and retired in 2004.

When she entered the military, she suppressed her feminine mannerisms and interests to adapt to the stringent, masculine environment, she said. She sometimes rented hotel rooms for a few hours so she could dress in the feminine clothing she longed to wear, away from judgmental bystanders.

It was the only place she could be herself, even if only momentarily.

In 1999, she moved to Maine to become a U.S. Department of Agriculture meat inspector. With her then-wife, she built a house on a plot of land in Hampden overlooking the Penobscot River. She designed it to reflect the principles of feng shui, the eastern art of placement, which she subscribed to as part of her Zen Buddhist beliefs.

Her vegetable garden beds lined each side of the house on steppes, as though they were the “wings of a dragon,” she said.

When she retired in 2018, she reflected on her life. After coming out to her wife, the decline of her already unraveling marriage accelerated. It hadn’t produced the children she wanted. Her former wife, whom she divorced earlier this month, declined to comment.

But those story endings meant a new one could begin. After nearly seven decades, it was time to become Lukcia.

Lukcia’s reality

At a dinner party in September, Lukcia meticulously dotted a ring of dill essential oil around plates containing chilled cucumber soup with jicama, watermelon and apples. She explained how the seasoning interacted with each ingredient to bring out the soup’s zesty flavor.

Dressed in her fuchsia chef’s coat, apron and cap, Lukcia held court for her guests, demonstrating how she simmered, boiled, braised, chopped, stewed and measured the ingredients to make gastronomical works of art like porchetta, roasted carrot soup and wild mushroom and bacon risotto.

After beginning her transition, Lukcia surrounded herself with a community of friends in their 20s, 30s and 40s. She often hosted people at her Hampden home, where she flexed the skills she picked up during a four-month stint at a southern Italian culinary school, freely pursuing a love of cooking that her father would once have forbidden.

Lukcia’s embrace of gourmet cooking and new set of friends represented one dimension of her transition into the person she always knew herself to be.

Some friends found that, within Lukcia’s story, they could see parts of their own. Shanna Saucier, 49, a frequent dinner party guest, met Lukcia at a bar in Bangor, shortly after Saucier separated from her husband. She was drawn to Lukcia’s gregarious nature and a shared sense that the two women were at major crossroads in their lives.

Clockwise from top left: Lukcia Sullivan gives a helping hand to Jamie Jurgiewich (left), 21, with shredding a block of parmesan romano cheese at a dinner party Lukcia was hosting at her Hampden home in March. In early 2021, Lukcia attended the Italian Culinary Institute in Calabria, Italy and earned a certificate of Master of Italian Cuisine; Lukcia keeps an eye on the risotto while Madisyn Billings (left) and Jurgiewich help with preparations; Dolce prepared by Lukcia at her dinner party was a carrot cake with carrot sorbet served with a dessert wine; Lukcia enjoys a dinner party with the company of new friends at her home; Lukcia visits with her friends Jurgiewich (far left) and Shanna Saucier at the dinner party. The photo in the background is from her five months at the institute. Credit: Linda Coan O’Kresik / BDN

“With my separation from my husband, I was finding my real self, and I was getting in touch with who Shanna really is,” Saucier said. “So there might be some kind of parallel where Lukcia and I were both finally taking a stance and, regardless of the ramifications, we’re just going to be who we are, who we need to be.”

Jamie Jurgiewich, another friend and frequent dinner party guest, saw Lukcia as almost her grandmother. The two met last summer at a Veazie store where Jurgiewich worked at the time.

“I feel like she’s going through some of the stages of being a girl that [I] went through or that maybe I’m currently going through,” Jurgiewich, 21, said.

Others have been less accepting. Maine has some of the nation’s strongest anti-discrimination laws, but that hasn’t always reflected Lukcia’s daily reality.

On one occasion, when Lukcia tried to strike up conversation with a woman at a bar, the woman’s date posed a series of confrontational questions, pressing for intrusive details about her surgeries and why she transitioned at such a late age, Lukcia said.

Some people won’t even sit near her. “I have people leave. They move one table away from me,” Lukcia said. “People can deal with concepts, but it’s difficult dealing with reality. I am reality.”

Other times the repercussions are deeply personal. A man she went on a few dates with broke things off after his friends criticized him for seeing a transgender woman. And a number of Lukcia’s relationships from earlier in life have also disappeared as she revealed more about her true identity.

But she never doubted her desire to transition.

“I just want to be a girl,” Lukcia said. “That’s all. I don’t understand it. I just know I want it. And I’ve wanted it my whole life.”

Coming out

For a long time Lukcia wanted to talk about her inner struggle. She tried to come out several times over 25 years to her family members and former spouse, and she was laughed off. But her retirement marked a turning point. She finally had the time and money to pursue her dreams.

First came culinary school in southern Italy, in January 2020, which COVID cut short after a month. The following year, when she was allowed to return, she told the school that she had been presenting as a woman for three months, and would do so for the duration of the course and beyond. The institute accepted her with few questions.

It was one step to becoming more public about her identity.

She emerged from her training in April 2021 not only knowledgeable about charcuterie arrangements and how to cook gourmet seafood and pasta, but with a desire to let the world around her Hampden home know who she really was.

Most of her and her then-wife’s friends and acquaintances did not know she had been presenting as a woman in her home since the previous fall, and it was time for them to know.

She put on her favorite matching pink blouse and skirt, and went to her butcher, pharmacist, the post office, grocery store and bike repair shop to reintroduce herself. Her transformation would not be complete without sharing it.

“I am Lukcia,” she said.

Lukcia Sullivan enjoys her first outing to Mason’s Brewing Company following her initial facial feminization surgery on Dec. 30, 2021. Lukcia met several of her new friends while eating there. After serving more than 20 years, Lukcia retired from the U.S. Army in 2004. She also served in the U.S. Coast Guard from January 1971 to December 1974. Credit: Linda Coan O’Kresik / BDN

Most accepted her right away. She attended her 50th high school class reunion later that summer, where everyone welcomed her as a transgender woman.

And she grew closer with Seymour, her sister, who visited last October. It was the first time they had seen each other in 12 years. Gone was the teenager Seymour remembered who effected macho behaviors to please their domineering father.

“I think we have a much better understanding of who we are,” Seymour said. “I’m much happier with it.”

At the same time, she worried for Lukcia’s safety, citing rising anti-transgender violence and the current political climate.

“I want the world to be kind to her, but I think we want the world to be kind to anybody we love,” Seymour said.

The two have since traveled back and forth between Maine and Georgia to visit each other.

In addition to two facial surgeries, Lukcia underwent a vaginoplasty in May, at the Papillon Gender Wellness Center in Pennsylvania. There, McGinn removed Lukcia’s testicles and constructed a vagina using existing genital tissue. Lukcia described this latter procedure as the “completion” of her medical transition.

Not all transgender people want or can afford the surgeries or hormonal treatments that Lukcia underwent. The three procedures, including associated travel and post-care expenses, like hired nurses, cost $143,000 out of pocket, which Lukcia paid using her savings and her military and USDA pensions.

Despite the financial cost, she compared the feeling after her first facial feminization surgery to floating on air.

“I already knew I was not going to turn back,” she said. “But I still had to come up with the courage to follow through, to know that the decision for me was correct. It was the first step of taking myself seriously and believing in my dream.”

Lukcia now dresses in the skirts she longed to wear for more than 60 years. She shrugs off the masculine mannerisms she struggled to parrot for decades. And she’s preparing for a future that includes her chosen family of those who support her. One day, she hopes it will include a loving companion.

She is also speaking out, in a direct reversal from her youth and later adult years.

When Lukcia first awoke on that December afternoon after her first facial surgery, her head was wrapped in bandages, and she was unable to talk because of heavy medication. She offered her foot to visitors who couldn’t touch her because of the risk of germs. She would spend her 69th birthday the following week at home, recovering.

She considered those minor inconveniences on a journey to embody the person she has always been.

“I laid down on that table. Then they strap you down to something that looks like a crucifix,” she said. “Then they look at you and go, ‘Are you ready?’ And I looked up to them and went, ‘I’ve been ready for so long.’”