On the heels of a report detailing how Twitter had once accidentally allowed a conspiracy theorist into its invite-only fact-checking program known as Birdwatch, the company is today announcing the program will expand to users across the U.S. — with a few changes. The rollout will add 1,000 more contributors to this program every week, ahead of the U.S. midterm elections. But Birdwatch won’t work the same as it did before, Twitter says.

Previously, Birdwatch contributors could immediately add their fact-checks to provide additional context to tweets. Now, that privilege will have to be earned.

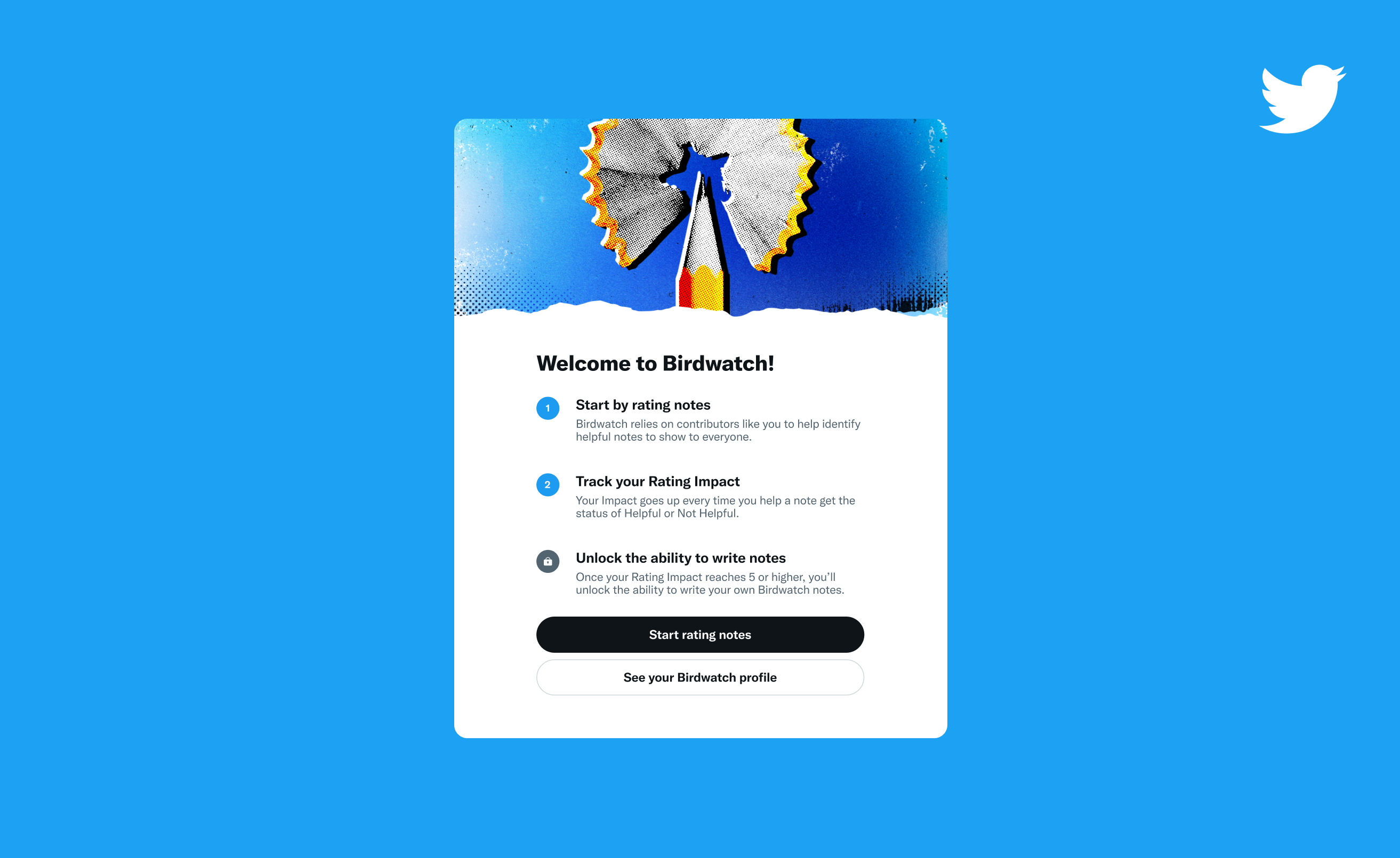

To become a Birdwatch contributor capable of writing “notes,” or annotations on tweets that provide further context, a person must first prove they’re capable of identifying the helpful notes written by others.

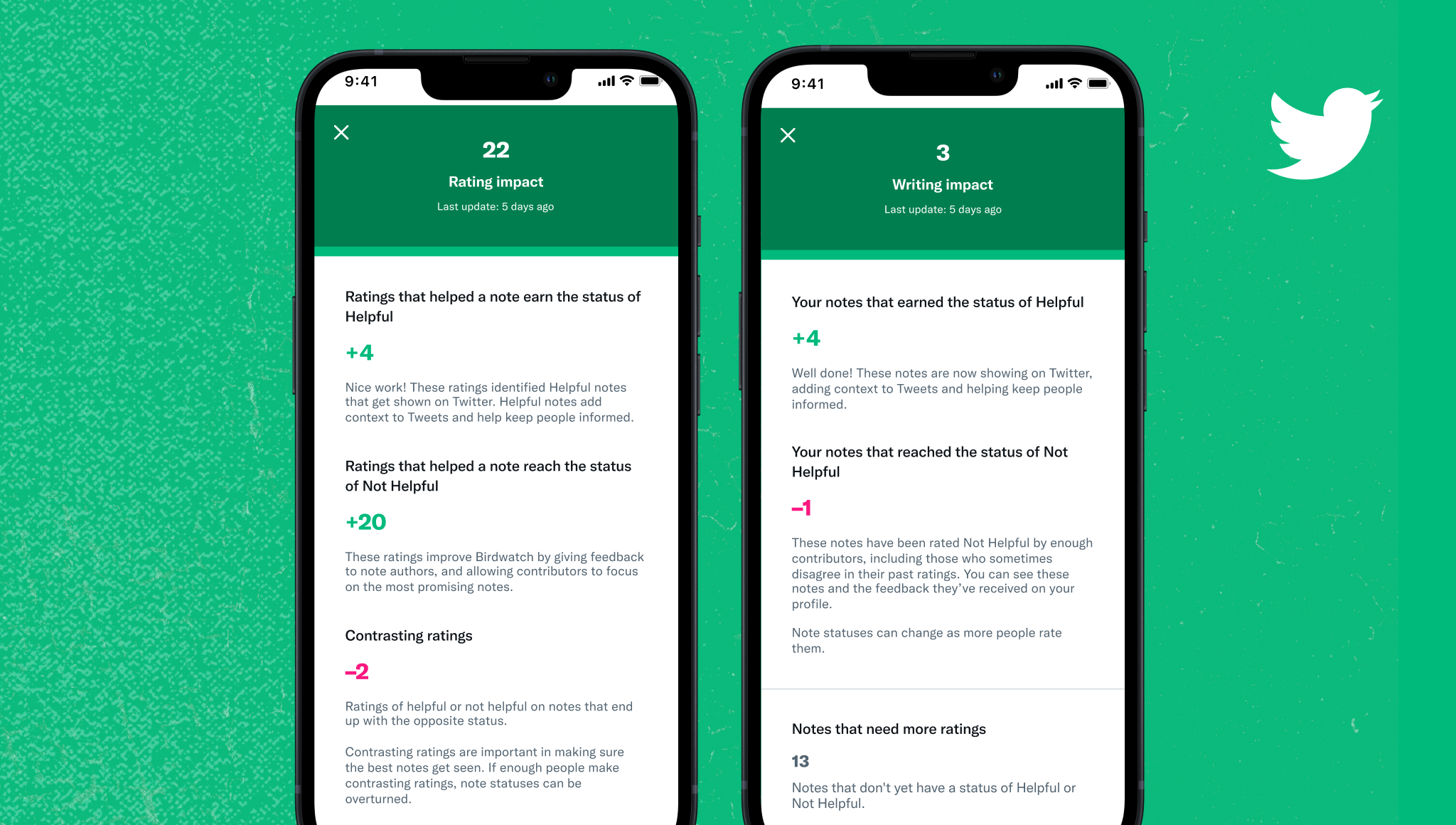

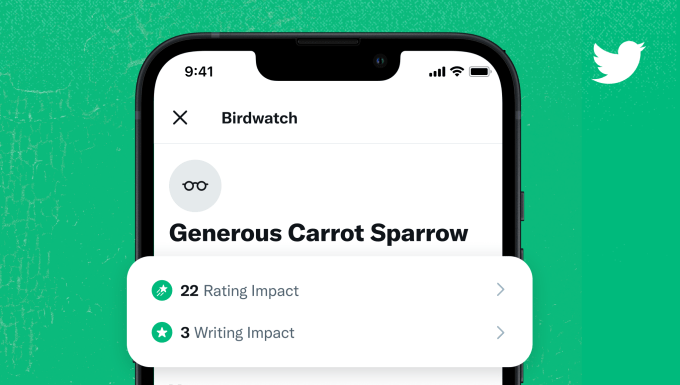

To determine this, Twitter will assign each potential contributor a “rating impact” score. This score begins at zero and must reach a “5” for a person to become a Birdwatch contributor — a metric that’s likely achievable after a week’s work, Twitter said. Users gain these points by rating Birdwatch notes that enable the note to earn the status of “Helpful” or “Not Helpful.” They lose points when their rating ends up in contrast with the note’s final status.

Image Credits: Twitter

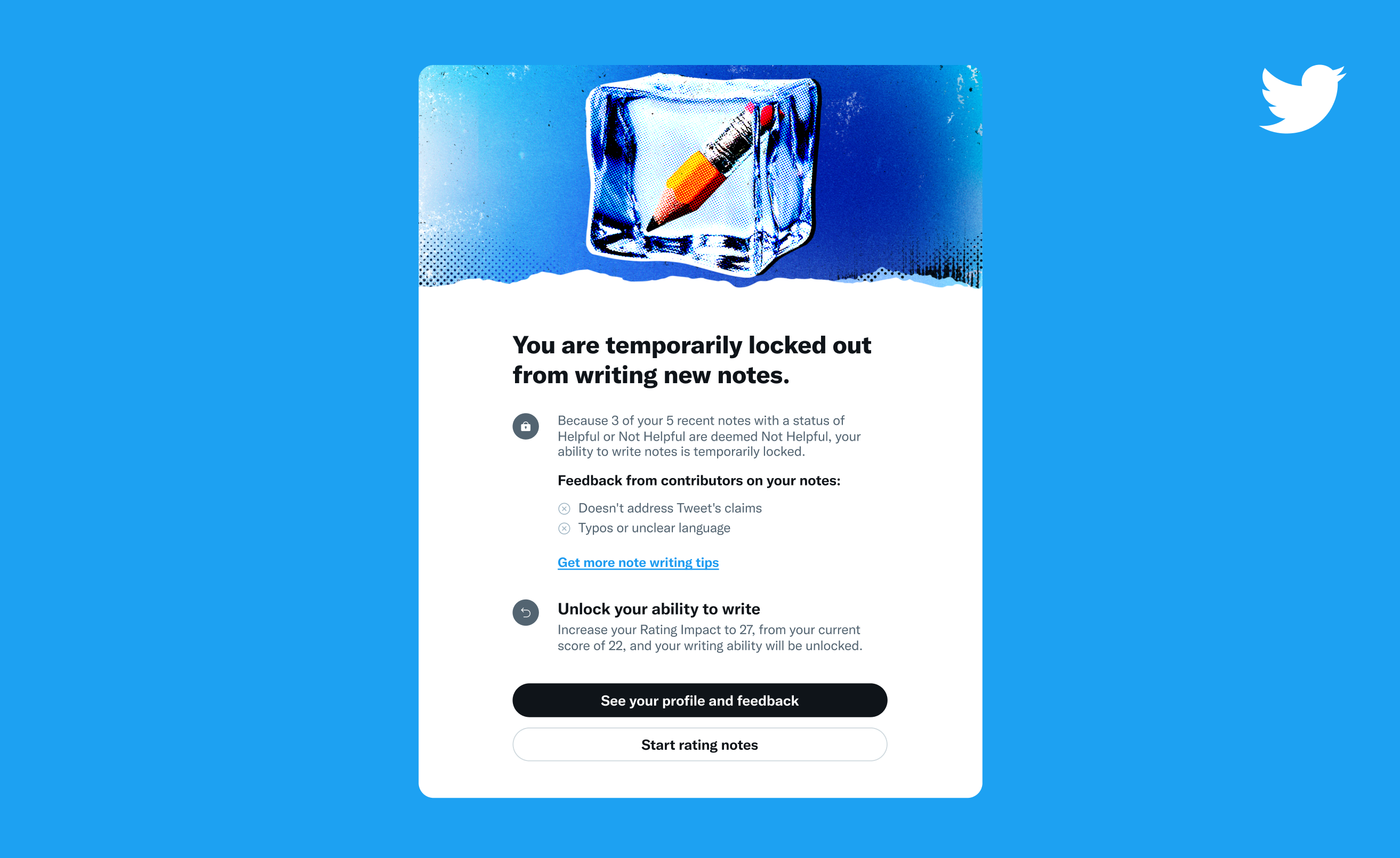

After a person unlocks the ability to write their own Birdwatch notes, they can begin adding contributions and fact-checks. But the quality of their work could lead them to lose their contributor status once again.

Twitter will first push the user whose notes are being marked “Not Helpful” to improve — by better addressing a tweet’s claims or by fixing typos, for instance. But if they still don’t improve, they will have their writing ability locked. They’ll then need to improve their rating impact score to become a contributor again.

Image Credits: Twitter

Another key aspect is how Birdwatch’s upgraded system involves the use of what the company is referring to as its “bridging algorithm.”

This works differently from many social media algorithms, said Twitter. Often, internet algorithms will determine which content to rate higher or approve based on whether or not there’s a majority consensus — like how a post that gets more upvotes on Reddit winds up at the top of the page, for instance. Or a platform may consider posts that meet certain thresholds for engagement — a factor Facebook considers, among others, when determining which posts make it into your feed.

Twitter’s bridging algorithm, on the other hand, will instead look to find consensus across groups where there are typically differing points of view before it highlights the crowd-sourced fact-checks to other users on its platform.

“To be shown on a tweet, a note actually has to be found helpful by people who have historically disagreed in their ratings,” explained Twitter Product VP Keith Coleman, in a briefing with reporters. The idea, he says, is that if people who tend to disagree on notes both find themselves agreeing that a particular note is helpful, that increases the chance that others will also agree about the note’s importance.

“This is a novel approach. We’re not aware of other areas where this has been done before,” Coleman said.

Twitter, however, did not invent this idea. Rather, the concept arose from academic research on internet polarization, where the idea for a bridging algorithm, or bridging-based ranking, is thought to be a potential approach to create a better consensus in a world where multiple truths sometimes seem to co-exist. Today, each side argues only their “truth” is true, and the other is a lie, which has made it difficult to find agreement. The bridging algorithm looks for areas where both sides agree. Ideally, platforms would then reward behavior that “bridges divides” rather than reward posts that create further division.

In the case of Birdwatch notes, Twitter claims to have already seen an impact since switching to this new scoring system during pilot tests.

It found that people on average were 20% to 40% less likely to agree with the substance of a potentially misleading tweet after they read the note about it.

This, said Coleman, is “really significant from the perspective of changing the understanding of a topic.”

Image Credits: Twitter

What’s more, the system works to find agreement across party lines, Twitter claims. It said there’s “no statistically significant difference” on this measure between Democrats, independents and Republicans.

Of course, this begs the question as to how many Birdwatch notes will actually make an appearance in the wild if they rely on cross-aisle agreement.

After all, there aren’t two truths. There is the truth and what another side wants to present as the truth. And there are a number of people on both sides of this equation, each armed with information that others who think like them will vote up and down (or Helpful or Not Helpful, as in Birdwatch’s case). This is the problem the internet delivered — one of a system where expertise and experience are discounted in favor of a crowd where the loudest voices on digital soapboxes get the most attention.

Birdwatch believes people will come to an agreement on certain points elevated by its crowdsourced fact-checkers as it finds common ground in the basis of fact, but this is ultimately the same promise that fact-checking organizations, like Politifact or Snopes, had promised. But when the facts they uncovered were misaligned with the narrative one side was espousing, the people on the losing team just pointed to the system overall as being corrupt.

How long Birdwatch will escape a similar fate is unknown.

But Twitter says it’s not rolling out Birdwatch more broadly to help counter election misinformation. It just believes the system is now ready to scale.

Plus, the company notes Birdwatch can be used to tackle all sorts of misleading content or misinformation outside of politics — including areas like health, sports, entertainment and other random curiosities that pop up on the internet — like whether or not someone just tweeted a photo of a bat the size of a human, for example.

Also during its pilot phase, Twitter found that people are 15% to 35% less likely to like or retweet a tweet when there’s a Birdwatch note attached to it, which reduces the further amplification of potentially misleading content in general.

“This is a really encouraging sign that, in addition to informing understanding, these Birdwatch notes are also informing people’s sharing behavior,” Coleman pointed out.

Image Credits: Twitter

This isn’t the first time Twitter has tweaked its Birdwatch system. Since launching its tests, it has added prompts that encouraged contributors to cite their sources when leaving notes and made it possible for users to contribute notes under an alias to minimize potential harassment and abuse. It also added notifications that let users know how many people have read their notes.

And while it allows users across Twitter to now rate notes, those ratings don’t change the outcome of the note’s availability — only ratings by Birdwatch contributors do.

The company’s partners, including AP and Reuters, will help Twitter to review the notes’ accuracy, but this won’t determine what shows up in Birdwatch. It’s a distributed system of consensus, not a top-down effort. However, Twitter says that during the 18 months it’s been piloting this project, the notes that were marked “Helpful” were generally those the partners also found to be accurate.

In addition, the Birdwatch algorithm as well as all contributions to the system are publicly available and open sourced on GitHub for anyone to access.

Twitter says it’s been piloting Birdwatch with around 15,000 contributors, but will now begin to scale the program by adding around 1,000 more contributors every week going forward. Anyone in the U.S. can qualify, but the additions will be on a first-come, first-serve basis. The notes can be written in both English and Spanish, but so far, most have chosen to write in the former.

To fight potential bots, Birdwatch contributors will also need to have a verified phone number from a mobile operator — not a virtual number. The accounts can’t have any recent rule violations and will need to be at least six months old.

Around half the U.S. user base will also start seeing the Birdwatch notes that reached the status of “Helpful,” starting today.

Twitter said the new system is not meant to replace its own fact-check labels or misinformation policies, but rather to run in tandem.

Today, the company’s misinformation policies cover a range of topics, from civic integrity to COVID and health misinformation to manipulated media, and more.

“Beyond those, there is still a lot of content out there that’s potentially misleading,” said Coleman. A tweet could be factually true but could leave out a detail that provides further context and impact how someone understood the topic, he suggested. “There’s no policy against that — and it’s really hard to craft policies in these gray areas,” Coleman continued.

“One of the powers of Birdwatch is that it can cover any tweet, it can cover any gray area. And ultimately, it’s up to the people to decide whether the context is helpful enough to be added,” he said.

Twitter expands its crowdsourced fact-checking program ‘Birdwatch’ ahead of US midterms by Sarah Perez originally published on TechCrunch