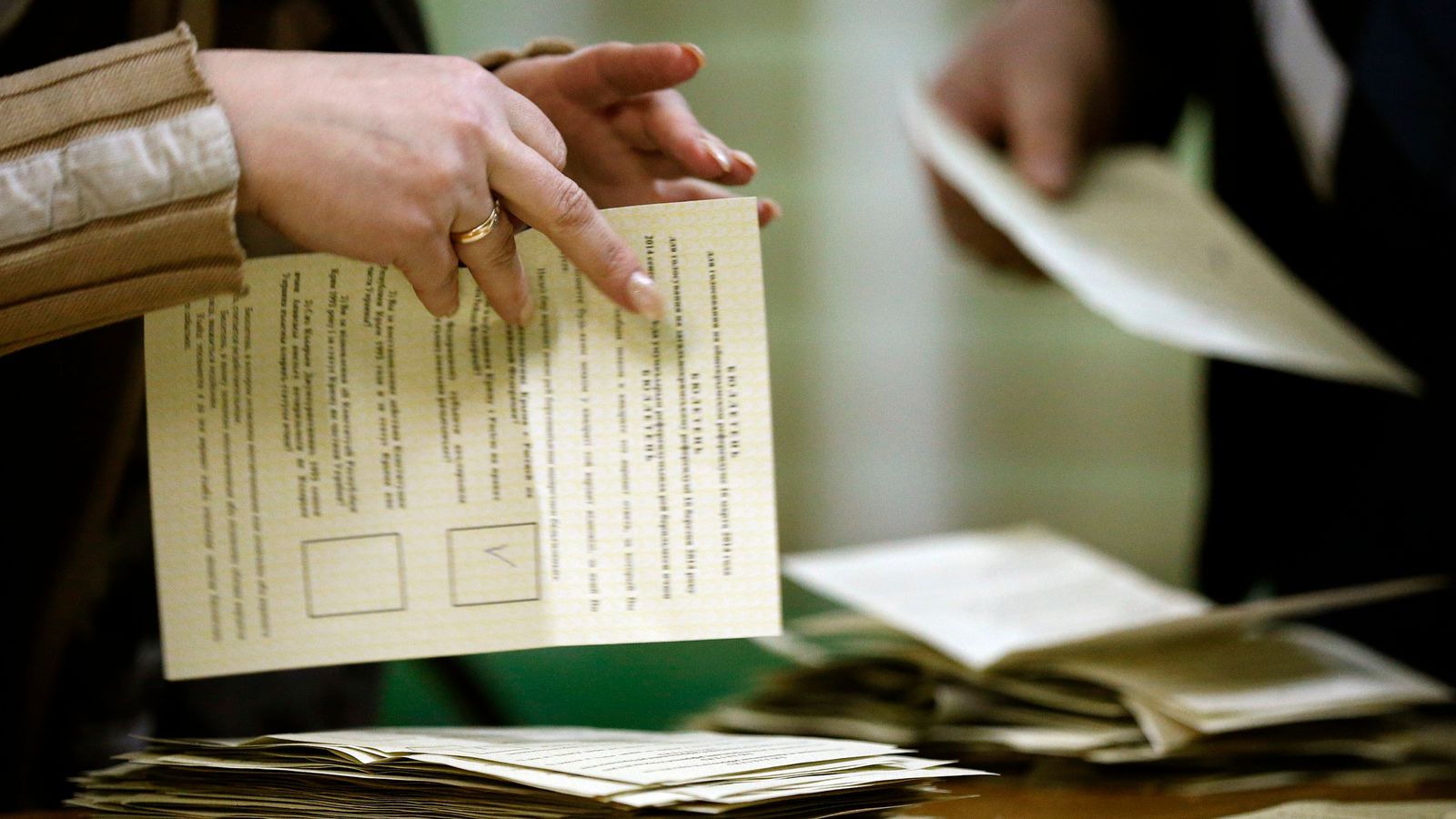

Vladimir Putin has given his explicit support to referenda that will be held in coming days in parts of Ukraine occupied by Russian forces.

They are due to be held in the self-declared Donetsk (DPR) and Luhansk People’s Republics (LPR), and in Russian-occupied parts of the Kherson and Zaporizhzhia regions.

It could lead to the formal annexation by Russia of about 15% of Ukrainian territory, an area slightly larger than Portugal.

The move comes eight years after a similar process in Russian-occupied Crimea, which Moscow said was justification for annexing the peninsula.

Russian troops, many acting incognito, invaded Crimea before Moscow-aligned local leaders announced and then carried out a vote that many said was illegitimate and illegal.

There are fears that the latest referenda to be announced will be similarly undemocratic.

Ukraine and Western countries have condemned the referendum plans as an illegal sham and made it clear they will never accept its results.

Ukraine invasion: What does Putin’s partial mobilisation order mean and what effect could it have on the war?

Putin warns West he isn’t bluffing and Russia has ‘lots of weapons’ – as he orders partial mobilisation of reserve troops to Ukraine

Why Ukraine’s southern offensive is proving more difficult than the blitzkrieg attack in the north | Stuart Ramsay

France’s president Emmanuel Macron said the plans for a vote were “a parody”.

What’s the precedent?

In February 2014, what was described at the time as mysterious little green men suddenly started appearing in the Ukrainian territory of Crimea, which to the world looked like Russian troops, but without any insignia on their fatigues.

While Crimea had been transferred to Ukraine in Soviet times, it has an ethnically Russian majority, and some welcomed the invaders.

At the time, the Kremlin flatly denied they were its troops, or that it was in the process of annexing part of another European country.

Ukraine was stunned and unable to act quickly or effectively enough to challenge the invaders.

Within days of the soldiers appearing, a new government had taken power – effectively installed by the occupying forces – which then declared independence from Ukraine and said it would carry out a referendum on the territory’s future.

The vote was decisive, with 97% across the Autonomous region of Crimea in favour of integrating the territory into the Russian Federation, with an 83% turnout, and within the local government of Sevastopol, 97% in favour of integration into Russia, with an 89% voter turnout.

Days after that, Vladimir Putin declared that Crimea was now part of Russia, despite widespread condemnation from the rest of the world.

The Ukrainian government, which had not long been in power after the Maidan revolution, was incensed, but lacked the military muscle to eject Russia from territory it was recognised as possessing under a series of international agreements.

The UN General Assembly passed a non-binding resolution declaring Crimea’s Moscow-backed referendum invalid, with 100 countries voting in favour, 11 against and 58 abstaining out of 193 nations, but little positive action was taken.

Many Western countries imposed sanctions, but Russia took them on the chin.

Events were quickly overtaken by separatists rising up and demanding independence in parts of Luhansk and Donetsk, with fighting that broke out there keeping the Ukrainian military occupied for the rest of the decade.

If Russia learned any lessons, it was that annexation could be achieved, if it acted in a way that meant any challenge to it would be limited.

In the aftermath of the Crimea referendum, the Russia-backed separatist governments in Luhansk and Donetsk organised their own polls, over the right to self-rule, but amid heavy international criticism, they fell short of offering Russian integration as an option.

Why a referendum?

While the referendum in Crimea was widely condemned, the result was decisive enough that Russia was able to claim that the people of the territory were in favour of joining the Federation.

Referenda have been used extensively in determining the future of territories where one portion of an electorate seeks independence, not least in Scotland in 2014.

The United Nations has backed referenda in many other countries that have sought independence from others, such as South Sudan and East Timor, based on the fundamental principle of the right of self-determination.

But, unlike in Crimea, and likely in the four Russia-occupied regions, many of those previous referenda have been supervised by independent international observers, to ensure they are held as fairly as possible.

While support for integration with Russia appears to have been strong, the results of the referendum in Crimea have been repeatedly questioned, as no international observers were present and the process took place so quickly.

Critics say the turnout was much lower than the 90-something per cent the Moscow-installed authorities claimed, and dissent is virtually non-existent due to the threat of what human rights groups say is a crackdown.

What’s going to happen?

Several of the Russia-occupied regions had said they planned to have referenda in the past, but had so far not been able to go ahead with them.

This time, Luhansk, Donetsk and Kherson officials said the referenda will take place between Friday 23 September and Monday 27 September.

Russia does not fully control any of the four regions, with only around 60% of the Donetsk region in Russian hands, which indicates only those in Russia-controlled areas will get to vote. In many of the areas Moscow does control, the ability of people to vote is likely to be restricted by wartime conditions.

In the event of a majority in those four regions voting to join Russia – probably regardless of whether the vote is seen internationally as legitimate – Mr Putin may well declare that they are now part of the Russian Federation.

What’s the danger?

If Moscow formally annexes an extra chunk of Ukraine, Vladimir Putin is essentially daring the United States and its European allies to risk a direct military confrontation with Russia, the world’s biggest nuclear power.

Mr Putin is using his nuclear arsenal as leverage.

Russia’s nuclear doctrine allows the use of such weapons if Russia faces an existential threat from conventional weapons or if weapons of mass destruction are used against it.

While there is no chance the West will use nuclear weapons against Russia as a first strike, Ukraine has been using conventional weapons to defend itself, firing into Russia-occupied territory to disrupt supply lines.

If those Russia-occupied territories are annexed and Mr Putin declares them to be part of Russia, any attack on the annexed territories could be interpreted as an attack on Russia.

This would give Mr Putin the potential pretext to use nuclear weapons in retaliation from Russia’s vast arsenal, which has more warheads than even the United States.

Dmitry Medvedev, who served as Russian president from 2008 to 2012 and is now deputy chairman of the Russian Security Council, said: “Encroachment onto Russian territory is a crime which allows you to use all the forces of self-defence.”