The good news was that European politicians did come up with an agreement about how to manage migration.

The bad news was that it felt like a very familiar sort of pact – they agreed that there was a problem, that it was serious and that something needed to be done.

But the thorny topic of exactly what new could be done – well, that has been left for another day.

What we did get was a demonstration of collective endeavour. The home secretary, Suella Braverman, was in Brussels, emphasising the political weight that she has placed on confronting migration. So, too, was the French interior minister, Gerald Darmanin, who talked of the “new co-operation” between the two countries.

But when the official announcement came, there was little sign of a big step forward – no new initiatives, or deployments. The most eye-catching statement was a hope that the UK would re-open negotiations with the European frontier agency, Frontex, on how best to work together.

But, perhaps, you could argue that what we got was a sign of a more thoughtful approach.

A realisation that the phenomenon of migration is not addressed by short-term fixes, but by a long-term view of how to address some fundamental questions – why do people move across Europe in the first place, how far do the tentacles of people-smuggling stretch, what is Europe’s responsibility for accepting migrants, and how should the continent’s frontiers be guarded?

Albanian ambassador calls for end to ‘campaign of discrimination’ – claiming Albanian children are being ‘bullied’ at school

‘TikTok traffickers’ who use videos to advertise Channel crossings must face criminal action – MP

Refugee trying to reach Europe shot near Bulgaria-Turkey border

“This is a collective problem and it needs a collective solution,” said Ms Braverman. “It has been a very constructive meeting between partners who are ultimately grappling with identical problems of illegal migration.”

The question of whether or not cross-Channel migration is actually illegal remains a thorny one. The United Nations maintains that the phrase should not be used, insisting that it cannot be illegal to claim asylum and that the term stigmatises refugees.

Ms Braverman maintains that cross-Channel crossings are facilitated by illegal gangs and allow people to enter the UK without permission. She has previously referred to the increase in cross-Channel migration as an “invasion”.

Ms Braverman told me: “There is a very strong character of criminality to these illegal migration routes. They are largely organised by criminal gangs and there is evidence that demonstrates people are arriving in the UK thanks to exploitation and people smugglers – criminal gangs that are very well co-ordinated and exploiting vulnerable people.

“We are all challenged right now by an increased number of people arriving in our respective countries illegally. We have challenges with bringing that down, challenges with resources, but we have a common recognition of that challenge.”

Please use Chrome browser for a more accessible video player

When I asked her French counterpart, Mr Darmanin, about the meeting, he seemed upbeat and positive, albeit while using a rather awkward turn of phrase. “I want to say to our British friends that we’re in the same boat,” he said. “We have work to do together to fight against illegal immigration.

“That involves fighting against the smugglers and traffickers, and I think we can celebrate the new co-operation with the British minister Suella Braverman.

“It’s obviously difficult, I don’t forget it’s difficult for the British people, it’s difficult for the French people. A large number of these migrants are in northern France and the French population have been putting up with this for more than 20 years.”

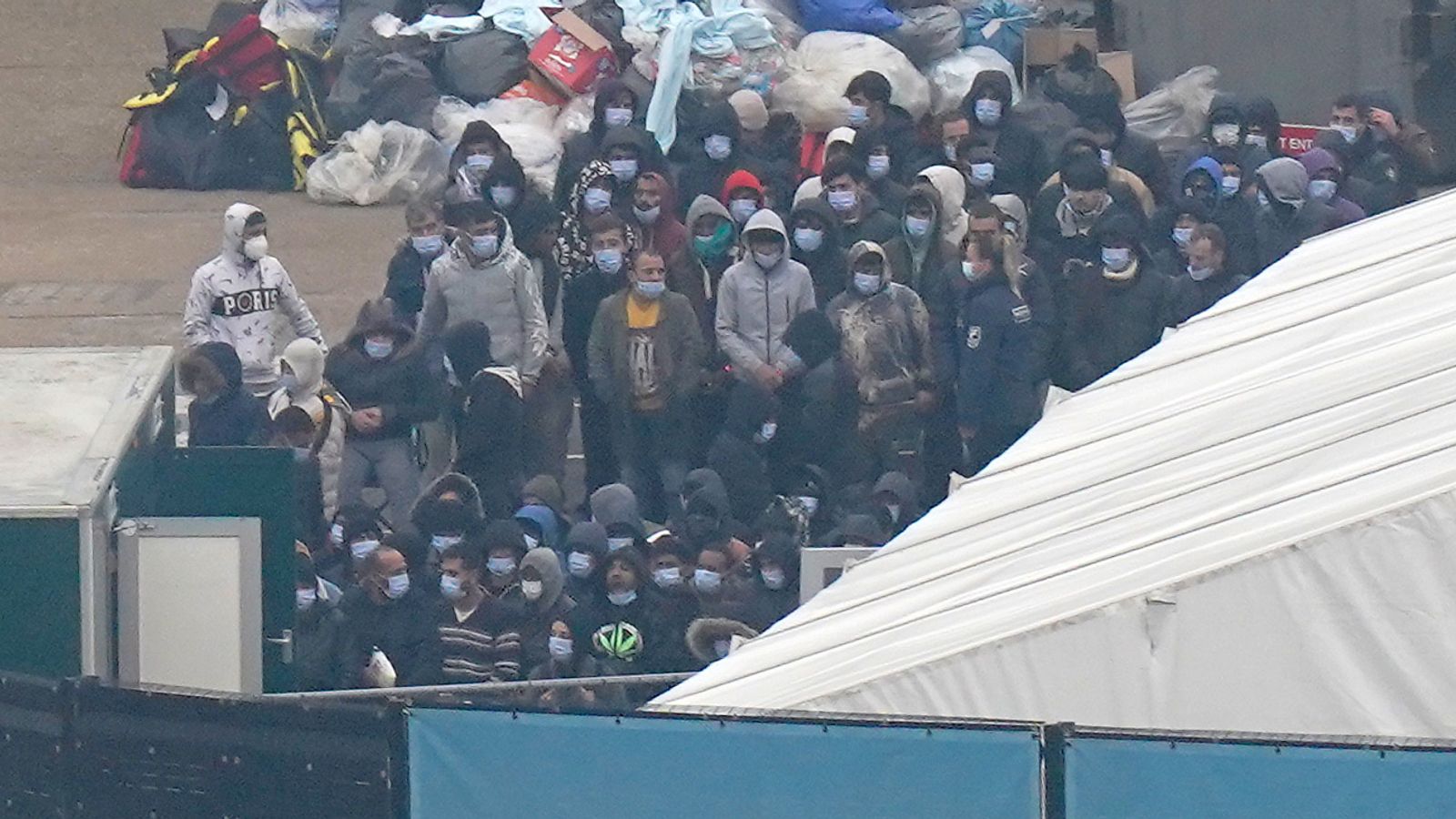

In northern France, around Calais and Dunkirk, there are still camps full of people trying to get to the UK. Two weeks ago, while filming at a sprawling, unpleasant site near the town of Grande-Synthe, we met Rebaz, who had spent months travelling from Kurdistan, despite the fact that his right leg has been amputated below the knee.

Now, Rebaz is in Britain, having crossed the Channel on a small boat. Speaking from a detention centre near Heathrow, he said he would not advise anyone to follow his path.

“I think no-one should take this journey,” he said. “No-one should take this sea route, it is very dangerous. That night our dinghy had no air and the engine was not working and we almost drowned.”

He has expected to be welcomed in the UK, not least because he says his injuries were the result of a NATO airstrike. Instead, he told us that the welcome had been cold.

“When I got to the UK, honestly, I thought they would treat me very well. But no one cared about me here. I have been here for eight days and no one cares.

“They know NATO hit me and I lost one leg and that my other leg, my back and my head are all injured. But now I don’t have any good feelings. They have not helped me at all. They just took me from the camp to this hotel and that is it. I ask them to help me, to take me to a better place and to give some extra attention to me as I am disabled. But they don’t care.”

It is a miserable testament but migration is often a miserable, traumatic experience. Europe’s leaders do seem to recognise that, and to understand the size of the problem. But what’s still not clear is the shape of their plan to change things.