A large hole capable of generating solar winds north of a million miles per hour has appeared on the surface of the sun for the second time in a week.

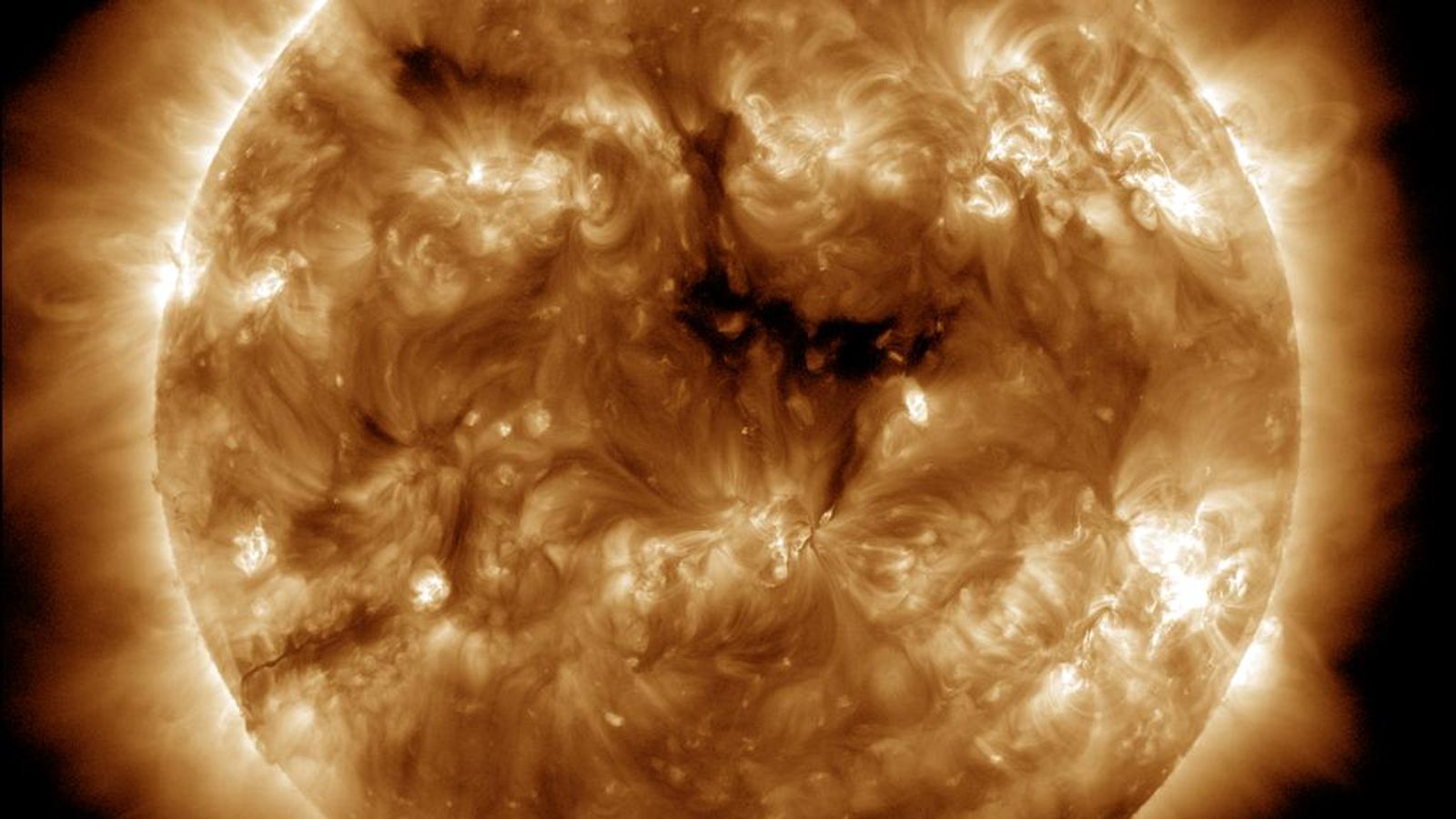

It is known as a coronal hole – and this one is 20 times bigger than Earth.

NASA’s Solar Dynamics Observatory spotted it, and it could send superfast solar winds of 1.8 million miles per hour hurtling towards our planet as early as Thursday.

In fact, the European Space Agency’s Solar Orbiter spacecraft has detected the winds already – travelling at some 700km per second as of Wednesday morning ahead of reaching Earth.

It has emerged just a week after an even bigger coronal hole was observed, which released such powerful winds it caused stunning displays of auroras in parts of the world.

But they do also have the potential impact on some infrastructure, chiefly satellites in the Earth’s orbit.

This week’s coronal hole is not expected to cause such damage – but scientists say we are in the midst of a period of heightened activity that we may need to be wary of.

Wait, are coronal holes a sign of trouble?

Not usually – in fact, they are incredibly normal.

As if to emphasise the point, last year NASA shared an image of a trio of holes making it look as though the sun was smiling down on us.

Daniel Verscharen, associate professor of space and climate physics at University College London, said they are a relatively common feature of the sun’s outer atmosphere – known as the corona.

“This one is special because it is near the sun’s equator,” he told Sky News.

“Since the sun rotates, an equatorial coronal hole can point towards the Earth at some point.”

But increased solar activity such as what we have seen in the past week is a sign of a more active sun.

Known as solar maximums, these periods come around every 11 years or so – prompting more holes and also more significant phenomena like coronal mass ejections (CMEs).

Prof Verscharen described it as the sun “waking up”.

What impact can solar winds have?

Solar winds are a flow of plasma launched at superfast speeds – 700 or 800 kilometres per second.

It’s potentially great news if you’re looking for a new phone background, as – when these winds collide with the Earth’s charged atmosphere – the result can be some magnificently bright auroras.

These are the beautiful natural sky shows made most famous by the Northern Lights.

They certainly look a lot prettier than the coronal holes themselves, which appear positively hellish (unless they are arranged like a smiley face).

The US’s National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, which monitors space weather, said they appear so dark because they are relatively cool and less dense than the surrounding areas of the sun.

Unfortunately, Prof Verscharen said this latest hole is unlikely to cause particularly bright auroras.

Please use Chrome browser for a more accessible video player

And what about satellites?

This is the main point of concern around intense solar activity.

Those aforementioned CMEs cause large expulsions of plasma and magnetic fields, and the geomagnetic storms that follow can sometimes impact satellite communications, which could become more disruptive as humans become increasingly reliant on them.

In the past, a solar storm has forced flights to be diverted.

The biggest such storm on record is known as the Carrington Event, which hit the Earth in 1859 and caused telegraph systems across America and Europe to fail.

We now have far more technology that would stand to be impacted by such an event.

Read more:

Could power on Earth be wiped out by a solar storm?

Please use Chrome browser for a more accessible video player

What else should you watch out for?

This “waking up” period we are now in is like hitting the jackpot if you’re an aurora watcher.

Prof Verscharen said: “Equatorial coronal holes, coronal mass ejections, and thus also aurorae are going to be more likely in the coming years.”

But what might cause a pretty light show for some could be potentially life-threatening for others.

The amount of radiation emitted by the sun can be extremely dangerous for astronauts going beyond the protection of Earth’s ionosphere – where the planet’s atmosphere meets space.

While the International Space Station falls within that boundary, any trips to the moon or beyond will go past it – and NASA is hoping to do just that in the years ahead.