Among the many tributes being paid to the late Conservative chancellor Nigel Lawson, perhaps the most striking came from Nicholas Macpherson, a former permanent secretary to the Treasury.

Lord Macpherson tweeted: “One of the great Chancellors of the 20th century.

“His microeconomic reforms particularly on tax were both daring and substantial, and have stood the test of time. His intellectual energy and openness to debate was inspirational in the Treasury of the 1980s.”

That is a huge testimony coming from someone who worked at HM Treasury for nearly 30 years and who served every chancellor from Lord Lawson to George Osborne.

Few people, regardless of their political persuasion, dispute Lord Lawson’s achievements.

Please use Chrome browser for a more accessible video player

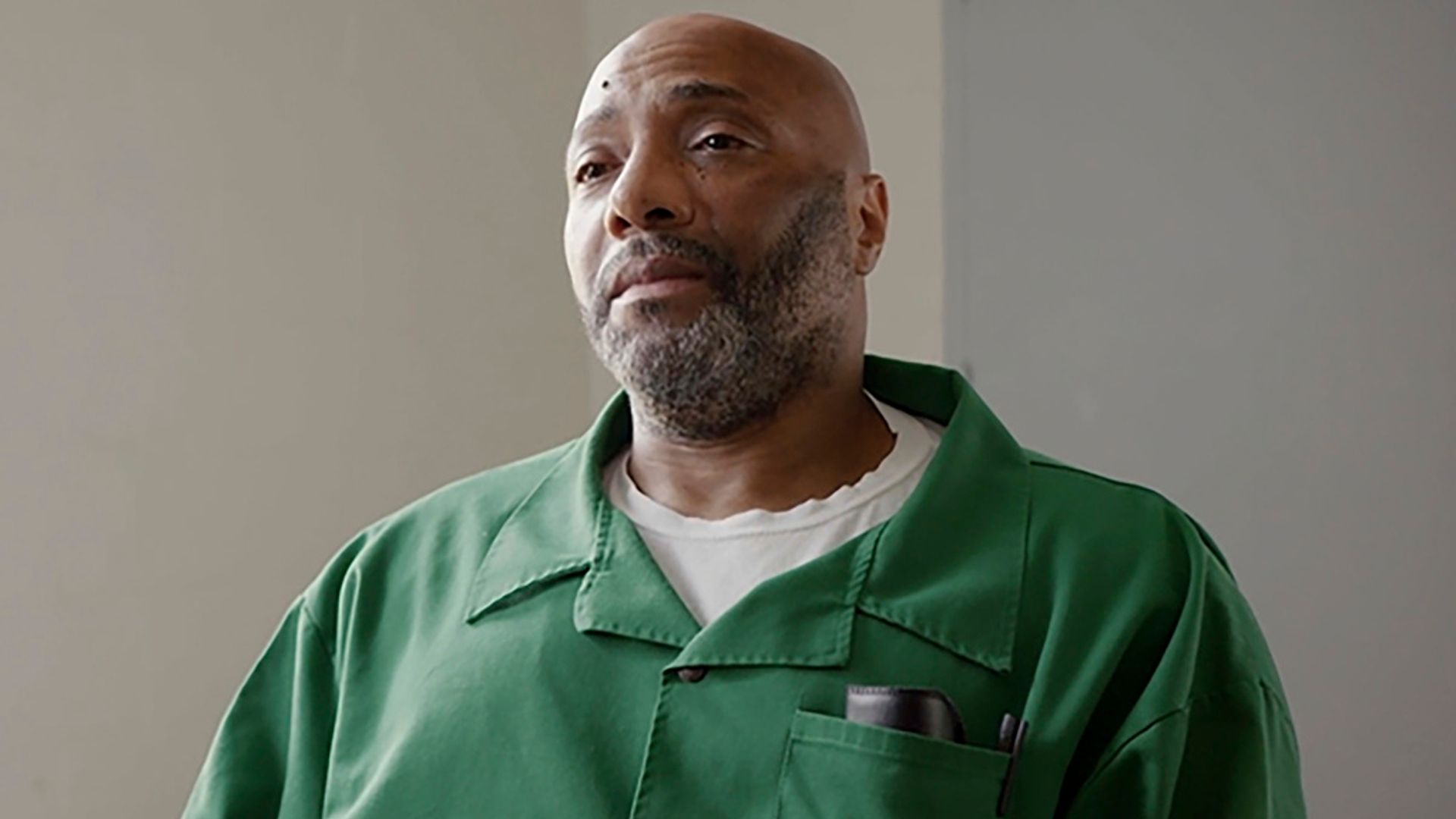

Rating the post-war chancellors

But where does he stand in the pantheon of post-war chancellors?

A very personal view is that, while Lawson (1983-89) was certainly one of the greatest post-war chancellors, he was not the greatest.

While he was an imaginative and courageous reformer, whose actions both inside and outside the Treasury undoubtedly boosted the competitiveness of the UK economy and the living standards of many Britons, he also presided over an inflationary over-heating in the economy that ultimately led to the recession of the early 1990s.

No, the accolade of Britain’s best post-war chancellor must surely go to his predecessor Geoffrey Howe (1979-1983), a reforming chancellor who did much of the heavy lifting that made possible Lawson’s later tax-cutting reforms.

Be the first to get Breaking News

Install the Sky News app for free

Life in the 1970s

For anyone who was not there at the time, it is almost impossible to describe the depths to which the UK economy had sunk during the late 1970s, the sheer state of decrepitude in the public finances and, indeed, the public realm.

Looking back, almost 40 years on, it is astonishing to think that Britons were once subject to foreign exchange controls limiting the amount of money they could take out of the country.

Changing that was one of Howe’s many reforms.

Despite his low-key demeanour, Howe was a radical, sweeping away not only controls on foreign exchange (a particularly revolutionary measure in which he had been encouraged by Lawson), but also on credit, pay and dividends.

He was also brave, daring to raise taxes in his 1981 budget, despite the country being in a recession at the time. It was a measure essential to restore order to the public finances even if it came at the price of hastening the deindustrialisation for which many on the left still despise the Conservatives.

A gift from Ken Clarke

Another Conservative of the 1979-1997 era, Ken Clarke (1993-1997), also deserves to rank highly among post-war chancellors.

Clarke, again, was a bold chancellor unafraid of taking tough decisions to strengthen the public finances.

The public sector borrowing requirement fell sharply during his time in office and, admittedly benefiting from a cheaper pound in the wake of ‘Black Wednesday’, he presided over a long period of unbroken growth in GDP.

Clarke bequeathed to his successor, Gordon Brown (1997-2007), an economy firing on all cylinders. Not that Brown appreciated it.

A fly-on-the-wall ITV documentary, covering his early weeks at the Treasury, captured a moment at which officials spelled out to the new chancellor just how strong an economy he had inherited. Brown growled in response: “What do you want me to do? Send a thank-you letter?”

Insufficient credit but also debits for Gordon Brown

Brown’s own record is decidedly mixed.

His greatest achievement was to hand operational independence to the Bank of England – at a stroke giving the financial markets confidence that the UK was serious about keeping inflation under control.

Interest rates were lower, as a result, than they would have been had they continued to be set by politicians.

That, and the strength of the public finances, enabled Brown to preside over one of the long periods of economic growth in British history.

Another fine achievement – one for which he probably does not receive sufficient credit – was resisting the urgings of Tony Blair, his prime minister, for Britain to join the eurozone.

In the debit column, Brown’s controversial tax raid on pensions early in his chancellorship did enormous and lasting damage to retirement savings in this country.

That very few private sector workers now enjoy gold-plated ‘final salary’ pensions now is a direct consequence of that raid.

It was also under Brown, who consistently borrowed more than he had previously forecast, that the progressive deterioration in the UK’s public finances began.

Brown also introduced more complexity into the tax code that hurt Britain’s competitiveness while his shake-up of financial regulation, stripping the Bank of regulatory oversight of the banking sector, was arguably a contributing factor behind why the UK suffered more damage from the global financial crisis than some of its peers.

Underrated chancellors

Some chancellors are under-rated at the time and especially at the time they leave office.

Into this category falls Norman Lamont (1990-1993), chancellor at the time of Black Wednesday, whose tenure at the Treasury is now more kindly regarded by economic historians now than it was by commentators at the time.

It also applies to Roy Jenkins (1967-1970), who restored stability to the economy following the devaluation crisis of November 1967, while also being unafraid to impose austerity despite it proving politically parlous.

Jenkins also left one of the most memorable and lasting quotes of any chancellor with his quip that inheritance tax is “a voluntary levy paid by those who distrust their heirs more than they dislike the Inland Revenue”.

Difficult to assess chancellor

Some chancellors are unfortunate in that their terms of office were just too short for a proper assessment of how well they did.

John Major (1989-1990) falls into that category, as do most of the chancellors of the 1950s, with the possible exception of Peter Thorneycroft (1957-1958), who is sometimes described as a ‘John the Baptist’ figure for Howe, such was his determination to bring public spending under control and bring order to the public finances.

Read more:

Former chancellor Nigel Lawson dies

The life of Thatcher’s chancellor, from political clashes to the Big Bang and climate scepticism

Be the first to get Breaking News

Install the Sky News app for free

Other chancellors are difficult to assess because their terms of office coincided with great national crises that make it hard to judge how well they might have done in other circumstances.

Some would argue that applies to Hugh Dalton (1945-1947) although it must be said that, over time, his tenure at the Treasury has become less kindly viewed.

It probably applies, though, to Alistair Darling (2007-2010), to whom fell the task of navigating the economy through the financial crisis and its aftermath and to Philip Hammond (2016-2019), the first chancellor to try to manage the economy as the UK went through the convulsions which followed the Brexit referendum.

But the one chancellor who did manage the economy through a crisis and who demonstrably succeeded in that task, though, is Howe.