AUGUSTA, Maine — Maine’s new plan to improve an embattled child welfare system will begin with a $1 million education program and continue with sweeping efforts to boost support for parents and children but few specifics on overall costs.

The first version of the state’s Child Safety and Family Well-Being Plan amounts to one of Gov. Janet Mills’ top policy statements on the child welfare system since she was elected in 2018. The issue has gained attention in fits and starts in the wake of well-publicized child deaths over the past several years that prompted frequent investigations and reviews of the system.

Officials with the Maine Department of Health and Human Services, which partnered with the Maine Child Welfare Action Network, did not answer questions during a Tuesday news conference called to roll out the plan about the total amount of money it will require or how many years it will take to implement.

“This is never going to be done,” Jeanne Lambrew, the commissioner of the Maine Department of Health and Human Services, told reporters. “It’s going to be a work in progress.”

State officials pitched it as a framework that will roll out formally in a spending plan and then be subject to frequent revisions going forward. It was the product of partnership with advocates and feedback from families, but a Republican lawmaker criticized the blueprint for vagueness.

Mills, a Democrat, teased the creation of the plan in her budget address in February. It largely consists of initiatives that the Legislature controlled by her party has already approved or is considering now, such as expanding affordable housing, reducing lead hazards, supporting transgender care and boosting access to behavioral health services for children.

Maine’s child welfare system has faced scrutiny before, from major reforms after 5-year-old Logan Marr’s death at the hands of her foster mother in 2001 and again after high-profile cases marked the end of former Gov. Paul LePage’s tenure and the beginning of the Mills era.

In 2021, 25 children died in incidents tracked by the state that were associated with abuse or neglect or after a history of family involvement with the child welfare system, which was the highest total on record. Maine’s child maltreatment rate was the highest in the country in 2020, according to a recent report from the Maine Children’s Alliance.

Mills and lawmakers responded in 2022 by adding more money for caseworkers and increasing the power of a state watchdog. The governor built on that in February by saying she wanted a substance use disorder expert in every child welfare district in Maine, a recovery coach pilot program to assist parents struggling with addiction and more Family Recovery Courts.

More specifics are expected in a spending plan that will be released by the governor soon. It is expected to contain new initiatives set aside by legislative Democrats when they passed a two-year state budget over Republican opposition in March, including $12 million for foster care and adoption assistance and $8 million for behavioral health care.

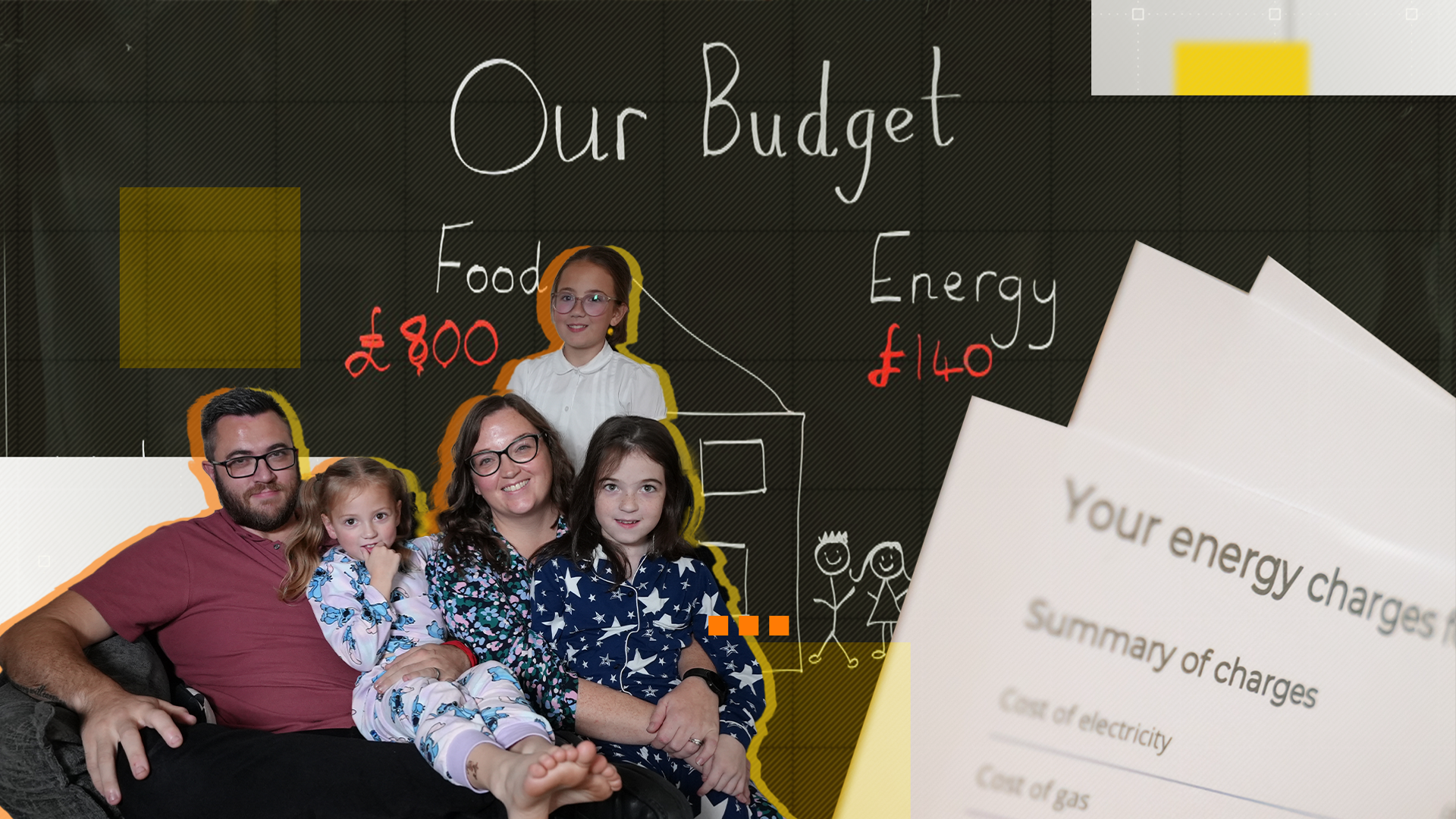

Lambrew and others who worked on the plan billed it as focusing on the holistic strategies of promoting supportive communities, improving parents’ economic security, aiding parents and caregivers and improving coordination of state and other kinds of services.

The Mills administration will make a budget request of $1 million to launch an education campaign aimed at parents “to reduce the stigma of asking for help.” About $300,000 would go toward direct education and over $700,000 would go toward supporting community agencies, Todd Landry, the director of the Maine Office of Child and Family Services, said.

The plan was also made in concert with the Maine Community Action Partnership. A survey of Maine families found a need to destigmatize seeking help and reduce long waitlists for behavioral and mental health care, early intervention services and child care, Megan Hannan, the group’s executive director, said.

Feedback from families also may push the state to modify its mandated reporter training to clarify when to call Child Protective Services to report suspected child abuse and when it is more appropriate to connect with other, non-punitive resources, officials said.

The political reaction to the plan was mixed. Reps. Michele Meyer, D-Eliot, and Michael Brennan, D-Portland, who co-chair the Legislature’s health and education committees, respectively, said in a joint statement it “lays out the path to strengthening families.”

But Sen. Jeff Timberlake, R-Turner, who is on the oversight panel that has been busy with probes of the child welfare system and attended Tuesday’s news conference announcing the plan, said state officials are “trying to show they’re doing something.”

“I don’t think I learned a whole lot,” Timberlake said in an interview. “How far does $1 million go in Maine? That’s nothing.”