At a virtual event this morning, Meta lifted the curtains on its efforts to develop in-house infrastructure for AI workloads, including generative AI like the type that underpins its recently launched ad design and creation tools.

It was an attempt at a projection of strength from Meta, which historically has been slow to adopt AI-friendly hardware systems — hobbling its ability to keep pace with rivals such as Google and Microsoft.

“Building our own [hardware] capabilities gives us control at every layer of the stack, from datacenter design to training frameworks,” Alexis Bjorlin, VP of Infrastructure at Meta, told TechCrunch. “This level of vertical integration is needed to push the boundaries of AI research at scale.”

Over the past decade or so, Meta has spent billions of dollars recruiting top data scientists and building new kinds of AI, including AI that now powers the discovery engines, moderation filters and ad recommenders found throughout its apps and services. But the company has struggled to turn many of its more ambitious AI research innovations into products, particularly on the generative AI front.

Until 2022, Meta largely ran its AI workloads using a combination of CPUs — which tend to be less efficient for those sorts of tasks than GPUs — and a custom chip designed for accelerating AI algorithms. Meta pulled the plug on a large-scale rollout of the custom chip, which was planned for 2022, and instead placed orders for billions of dollars’ worth of Nvidia GPUs that required major redesigns of several of its datacenters.

In an effort to turn things around, Meta made plans to start developing a more ambitious in-house chip, due out in 2025, capable of both training AI models and running them. And that was the main topic of today’s presentation.

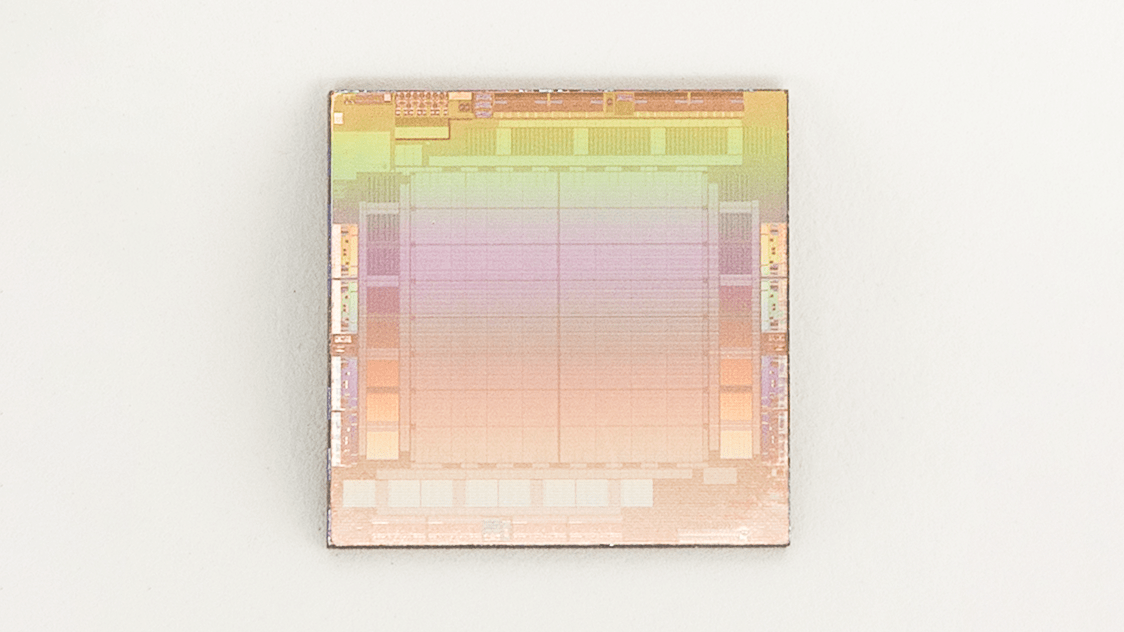

Meta calls the new chip the Meta Training and Inference Accelerator, or MTIA for short, and describes it as a part of a “family” of chips for accelerating AI training and inferencing workloads. (“Inferencing” refers to running a trained model.) The MTIA is an ASIC, a kind of chip that combines different circuits on one board, allowing it to be programmed to carry out one or many tasks in parallel.

An AI chip Meta custom-designed for AI workloads.

“To gain better levels of efficiency and performance across our important workloads, we needed a tailored solution that’s co-designed with the model, software stack and the system hardware,” Bjorlin continued. “This provides a better experience for our users across a variety of services.”

Custom AI chips are increasingly the name of the game among the Big Tech players. Google created a processor, the TPU (short for “tensor processing unit”), to train large generative AI systems like PaLM-2 and Imagen. Amazon offers proprietary chips to AWS customers both for training (Trainium) and inferencing (Inferentia). And Microsoft, reportedly, is working with AMD to develop an in-house AI chip called Athena.

Meta says that it created the first generation of the MTIA — MTIA v1 — in 2020, built on a 7-nanometer process. It can scale beyond its internal 128MB of memory to up to 128GB, and in a Meta-designed benchmark test — which, of course, has to be taken with a grain of salt — Meta claims that the MTIA handled “low-complexity” and “medium-complexity” AI models more efficiently than a GPU.

Work remains to be done in the memory and networking areas of the chip, Meta says, which present bottlenecks as the size of AI models grow, requiring workloads to be split up across several chips. (Not coincidentally, Meta recently acquired an Oslo-based team building AI networking tech at British chip unicorn Graphcore.) And for now, the MTIA’s focus is strictly on inference — not training — for “recommendation workloads” across Meta’s app family.

But Meta stressed that the MTIA, which it continues to refine, “greatly” increases the company’s efficiency in terms of performance per Watt when running recommendation workloads — in turn allowing Meta to run “more enhanced” and “cutting-edge” (ostensibly) AI workloads.

A supercomputer for AI

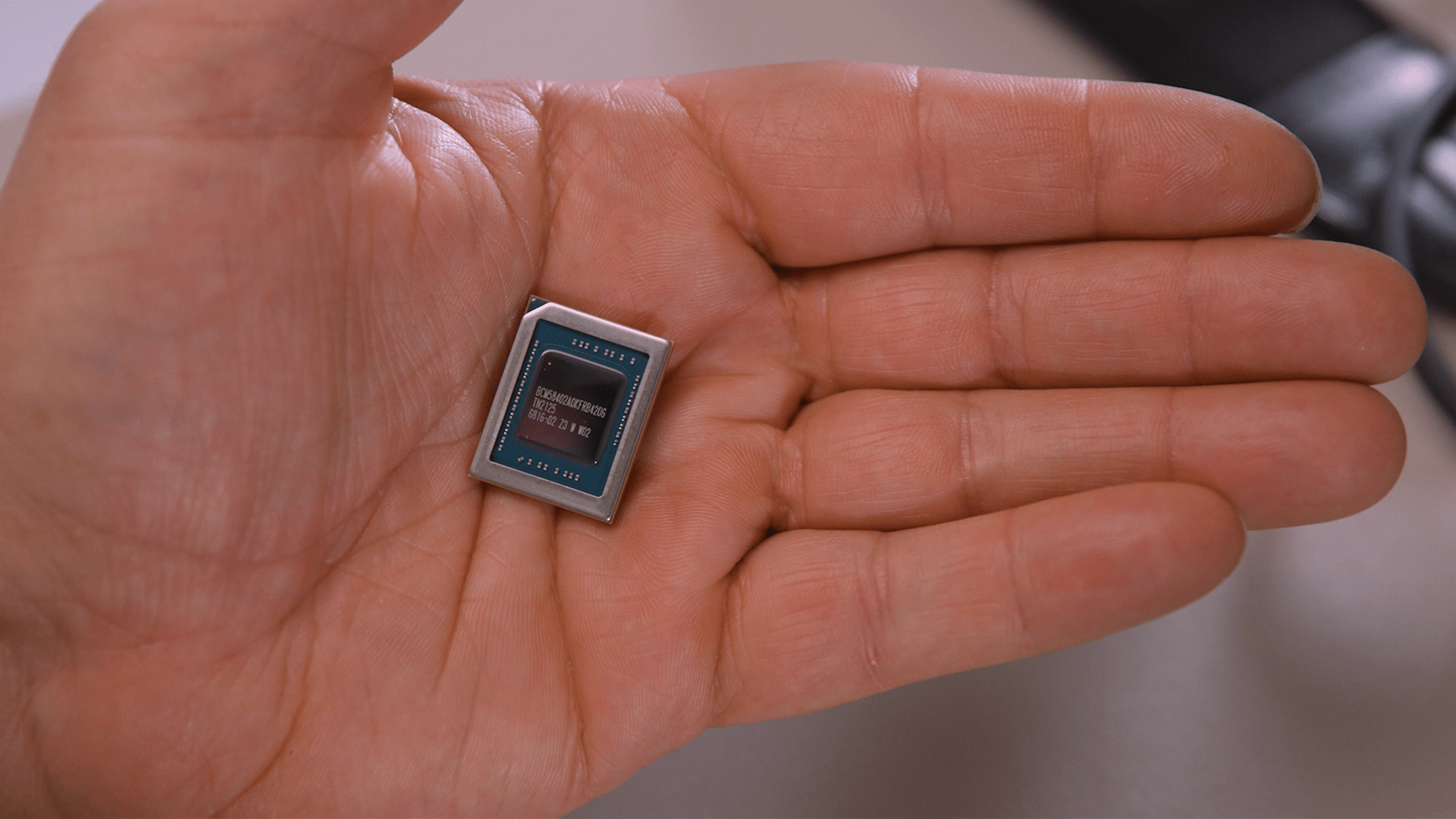

Perhaps one day, Meta will relegate the bulk of its AI workloads to banks of MTIAs. But for now, the social network’s relying on the GPUs in its research-focused supercomputer, the Research SuperCluster (RSC).

First unveiled in January 2022, the RSC — assembled in partnership with Penguin Computing, Nvidia and Pure Storage — has completed its second-phase buildout. Meta says that it now contains a total of 2,000 Nvidia DGX A100 systems sporting 16,000 Nvidia A100 GPUs.

So why build an in-house supercomputer? Well, for one, there’s peer pressure. Several years ago, Microsoft made a big to-do about its AI supercomputer built in partnership with OpenAI, and more recently said that it would team up with Nvidia to build a new AI supercomputer in the Azure cloud. Elsewhere, Google’s been touting its own AI-focused supercomputer, which has 26,000 Nvidia H100 GPUs — putting it ahead of Meta’s.

Meta’s supercomputer for AI research.

But beyond keeping up with the Joneses, Meta says that the RSC confers the benefit of allowing its researchers to train models using real-world examples from Meta’s production systems. That’s unlike the company’s previous AI infrastructure, which leveraged only open source and publicly available data sets.

“The RSC AI supercomputer is used for pushing the boundaries of AI research in several domains, including generative AI,” a Meta spokesperson said. “It’s really about AI research productivity. We wanted to provide AI researchers with a state-of-the-art infrastructure for them to be able to develop models and empower them with a training platform to advance AI.”

At its peak, the RSC can reach nearly 5 exaflops of computing power, which the company claims makes it among the world’s fastest. (Lest that impress, it’s worth noting some experts view the exaflops performance metric with a pinch of salt and that the RSC is far outgunned by many of the world’s fastest supercomputers.)

Meta says that it used the RSC to train LLaMA, a tortured acronym for “Large Language Model Meta AI” — a large language model that the company shared as a “gated release” to researchers earlier in the year (and which subsequently leaked in various internet communities). The largest LLaMA model was trained on 2,048 A100 GPUs, Meta says, which took 21 days.

“Building our own supercomputing capabilities gives us control at every layer of the stack; from datacenter design to training frameworks,” the spokesperson added. “RSC will help Meta’s AI researchers build new and better AI models that can learn from trillions of examples; work across hundreds of different languages; seamlessly analyze text, images, and video together; develop new augmented reality tools; and much more.”

Video transcoder

In addition to MTIA, Meta is developing another chip to handle particular types of computing workloads, the company revealed at today’s event. Called the Meta Scalable Video Processor, or MSVP, Meta says that it’s its first in-house-developed ASIC solution designed for the processing needs of video on demand and live streaming.

Meta began ideating custom server-side video chips years ago, readers might recall, announcing an ASIC for video transcoding and inferencing work in 2019. This is the fruit of some of those efforts, as well as a renewed push for a competitive advantage in the area of live video specifically.

“On Facebook alone, people spend 50% of their time on the app watching video,” Meta technical lead managers Harikrishna Reddy and Yunqing Chen wrote in a co-authored blog post published this morning. “To serve the wide variety of devices all over the world (mobile devices, laptops, TVs, etc.), videos uploaded to Facebook or Instagram, for example, are transcoded into multiple bitstreams, with different encoding formats, resolutions and quality … MSVP is programmable and scalable, and can be configured to efficiently support both the high-quality transcoding needed for VOD as well as the low latency and faster processing times that live streaming requires.”

Meta’s custom chip designed to accelerate video workloads, like streaming and transcoding.

Meta says that its plan is to eventually offload the majority of its “stable and mature” video processing workloads to the MSVP and use software video encoding only for workloads that require specific customization and “significantly” higher quality. Work continues on improving video quality with MSVP using preprocessing methods like smart denoising and image enhancement, Meta says, as well as post-processing methods such as artifact removal and super-resolution.

“In the future, MSVP will allow us to support even more of Meta’s most important use cases and needs, including short-form videos — enabling efficient delivery of generative AI, AR/VR and other metaverse content,” Reddy and Chen said.

AI focus

If there’s a common thread in today’s hardware announcements, it’s that Meta’s attempting desperately to pick up the pace where it concerns AI, specifically generative AI.

As much had been telegraphed prior. In February, CEO Mark Zuckerberg — which has reportedly made upping Meta’s compute capacity for AI a top priority — announced a new top-level generative AI team to, in his words, “turbocharge” the company’s R&D. CTO Andrew Bosworth likewise said recently that generative AI was the area where he and Zuckerberg were spending the most time. And chief scientist Yann LeCun has said that Meta plans to deploy generative AI tools to create items in virtual reality,

“We’re exploring chat experiences in WhatsApp and Messenger, visual creation tools for posts in Facebook and Instagram and ads, and over time video and multi-modal experiences as well,” Zuckerberg said during Meta’s Q1 earnings call in April. “I expect that these tools will be valuable for everyone from regular people to creators to businesses. For example, I expect that a lot of interest in AI agents for business messaging and customer support will come once we nail that experience. Over time, this will extend to our work on the metaverse, too, where people will much more easily be able to create avatars, objects, worlds, and code to tie all of them together.”

In part, Meta’s feeling increasing pressure from investors concerned that the company’s not moving fast enough to capture the (potentially large) market for generative AI. It has no answer — yet — to chatbots like Bard, Bing Chat or ChatGPT. Nor has it made much progress on image generation, another key segment that’s seen explosive growth.

If the predictions are right, the total addressable market for generative AI software could be $150 billion. Goldman Sachs predicts that it’ll raise GDP by 7%.

Even a small slice of that could erase the billions Meta’s lost in investments in “metaverse” technologies like augmented reality headsets, meetings software and VR playgrounds like Horizon Worlds. Reality Labs, Meta’s division responsible for augmented reality tech, reported a net loss of $4 billion last quarter, and the company said during its Q1 call that it expects “operating losses to increase year over year in 2023.”

Meta bets big on AI with custom chips — and a supercomputer by Kyle Wiggers originally published on TechCrunch