We all have difficult neighbours – even the Earth.

Now scientists have found that a planet close to our own world stinks of rotten eggs.

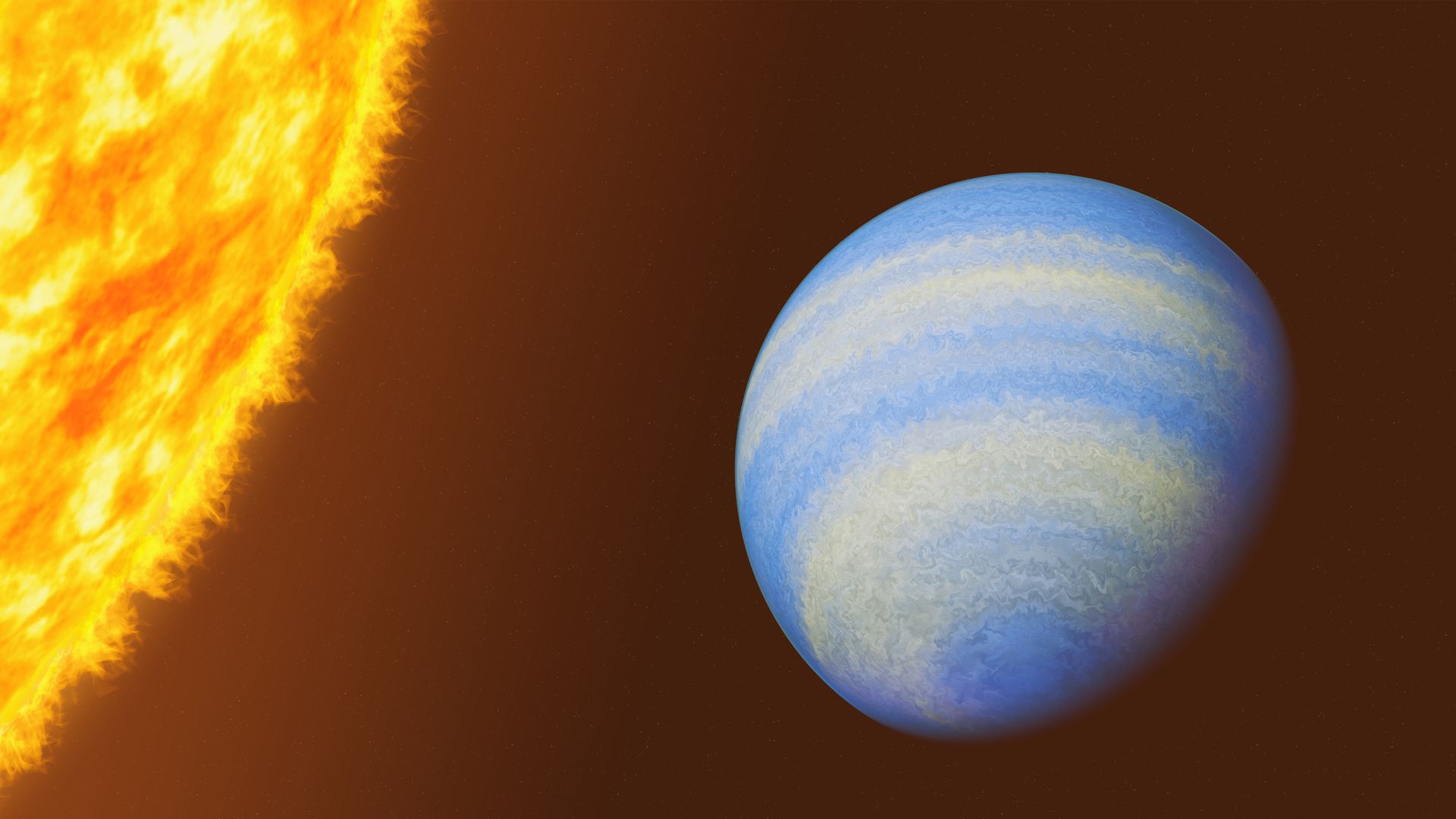

The research, from scientists at the Johns Hopkins University in the US, suggests that the atmosphere of the planet HD 189733 b, a Jupiter-sized gas giant, has trace amounts of hydrogen sulphide.

HD 189733 b is an exoplanet – meaning it is outside our solar system.

The discovery of hydrogen sulphide on the exoplanet offers scientists new clues about how sulphur, a building block of planets, might influence the insides and atmospheres of exoplanets.

At only 64 light-years from Earth, HD 189733 b is the nearest “hot Jupiter” astronomers can observe passing in front of its star.

The planet also has extremely high temperatures of about 927C and is known for vicious weather, including raining glass that blows sideways on winds of 5,000mph.

Guangwei Fu, an astrophysicist at Johns Hopkins University, said: “Hydrogen sulphide is a major molecule that we didn’t know was there.

“We predicted it would be, and we know it’s in Jupiter, but we hadn’t really detected it outside the solar system.

“We’re not looking for life on this planet because it’s way too hot, but finding hydrogen sulphide is a stepping stone for finding this molecule on other planets and gaining more understanding of how different types of planets form.”

Read more:

Asteroid to pass Earth ‘in relatively close shave’

‘Super moss’ could sustain life on Mars

NASA volunteers released after spending year in Mars bunker

The planet was discovered in 2005, and since then has been important for detailed studies of exoplanetary atmospheres.

The new data is from the James Webb Space Telescope and was published in the journal Nature. The research also ruled out the presence of methane in HD 189733 b.

Keep up with all the latest news from the UK and around the world by following Sky News

Be the first to get Breaking News

Install the Sky News app for free

“We had been thinking this planet was too hot to have high concentrations of methane, and now we know that it doesn’t,” Mr Fu said.

The researchers hope to track sulphur in more exoplanets and determine how high levels of that compound might influence how close they form near their parent stars.