In early colonial times, when European settlers first started dining on our state’s most famous crustaceans, lobster fishing wasn’t difficult.

It wasn’t even fishing.

“Lobsters could be picked up along the shores but were not much esteemed as food,” wrote Nell S. Thompson in her book “Traditions and Records of Southwest Harbor and Somesville, Mount Desert Island, Maine” in 1938.

Actual lobster traps didn’t make the scene until the dawn of the 19th century.

Ebenezer Thorndike of Swampscott, Massachusetts, is thought to have invented the first American lobster trap in 1808. Thorndike was a cobbler who owned a fish market on the side in Charleston, Massachusetts.

The traps made Thorndike a very rich man, and it wasn’t long before the cobbler’s inventions made their way to Maine waters, where they’ve been fueling the local economy ever since.

These days, lobster fishing technology is still in the news.

Federal fishery regulators are currently trying to reduce fishing gear entanglement risks for the remaining 350 right whales on the east coast, eyeing a 90 percent reduction, in order to comply with the Endangered Species Act.

Local lobstermen have already altered much of their gear in service to that effort but even more drastic changes may be coming.

While that’s getting decided, let’s take a look at some historic pictures from the Penobscot Marine Museum’s vast photo collection showing Maine lobster gear through the years.

Days of wood

In early days, both traps and buoys were made of wood. A lobsterman named O.W. Whitaker owned this weatherworn, wooden buoy. Not much else is known about the artifact, according to the museum catalog. It would have been hand carved, without the use of a spinning lathe, and possibly painted.

In March 1955, Maine painter, printmaker and photographer Carroll Thayer Berry shot pictures at Lee Hawkins’ saw mill, somewhere on the coast. In Berry’s photos, men rough out wooden lobster buoys with a hatchet before finishing them on a fast-turning lathe. Wood chips fly into the air and cover the floor.

The Penobscot Marine Museum holds a huge collection of Berry’s work, including more than 9,000 negatives, 4,300 prints, hundreds of slides and 28 working sketches for wood block prints and screens.

Nationally known Maine photographer Kosti Ruohomaa shot a picture of Spruce Head lobsterman Alvin Rackliffe and Rackliffe’s son Lanny for a 1958 issue of Maine Coast Fisherman magazine. The pair were second- and third-generation lobster hunters.

In the photo, the Rackliffes look at a wooden lobster buoy sitting on a wooden trap.

At the time, Alvin Rackliffe was a member of the new, 2,300-member Maine Lobstermen’s Association, which was being investigated by the FBI for price fixing. The association’s members had agreed to tie up for a week in hopes of raising the price of lobster.

It worked.

But the U.S. the Department of Justice took the fishermen to court, where a judge forbade lobstermen from engaging in any efforts to “reduce, curtail or limit the catch or supply of live Maine lobsters.”

This decree remained in effect for more than 50 years. In 2010, the Maine Lobstermen’s Association fought to have the decision terminated. It was finally lifted in 2014, though the organization is still prevented from anything resembling price fixing by federal antitrust laws.

In 1958, well-known lobsterman Ote Lewis of Ash Point (between Spruce Head and Owls Head in Knox County) was photographed with a wooden lobster trap for one of the National Fisherman magazines.

Lewis was one of the founders of the Maine Lobster Festival. In the photo he has a hand on a new fangled, double-chamber trap, though it still appears to have an old fashioned, rounded top.

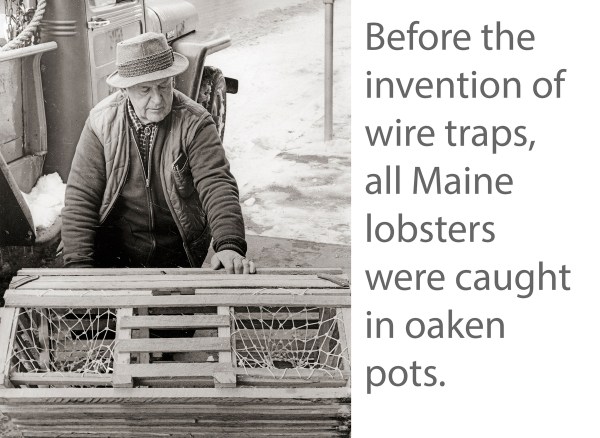

Wooden lobster traps were always made from oak and originally had rounded tops, maximizing volume while minimizing weight. In the days when waterlogged traps were hauled by hand, it was an important consideration.

“It could be built relatively quickly by the fisherman, ” reads an online exhibit at the Marine Museum website. “Bricks on the base ensured that it landed bottom down. These traps had a limited lifespan, soaking up water and being susceptible to worm and other marine life damage.”

Later, after mechanical haulers were invented, weight became less of an issue and flat-topped traps became the norm. Flat tops were also easier to stack.

In the early 1970s, Everett L. “Red” Boutilier photographed Bremen lobsterman Burt Carter. In one photo, Carter is still using a round-topped trap and his bait barrel and boat are wooden, as well. The lobsterman does have a mechanical “snatch block” trap hauler installed.

Also in the photo are Carter’s son Paul and two young men with long hair from New York, one of which holds baitfish on a spiked “bait iron.”

Boutilier was a prolific freelance photographer from Lincoln County. Born in 1918 he spent time working on some of the last east coast fishing schooners. He was also a newspaperman in Maine, New York, Kentucky and Florida. The Marine Museum has custody of Boutilier’s entire photographic collection, comprising more than 15,000 negatives.

To plastic and wire

Eventually, in the 1980s and ’90s, plastic and foam models replaced wooden buoys, while plastic-coated wire traps superseded traditional oak.

James Knott Sr. of Brookline, Massachusetts is credited with inventing the wire trap in 1956. They took a while to catch on but nowadays, being at least 100 pounds lighter than a sodden, wooden trap, they’re the only ones being built.

“Today’s wire lobster traps are relatively standard in shape and design, as they are mass produced by commercial trap builders,” wrote Christina Lemieux Oraganoin her 2012 book “How to Catch a Lobster in Down East Maine.”

Wooden traps were meant to last a season or two. Wire traps can last a decade, which can make lost “ghost gear” an ongoing ocean floor menace.

In an undated, but likely 1980s vintage, photo in the Marine Museum’s National Fisherman collection, a man wearing a “Betts Trap” cap poses with a wire trap inside what looks like a workshop.

It’s unclear where the photo was taken but it’s probably in Maine. Bett’s is a common coastal surname still associated with lobster fishing.

In another photo, dated 1981, Hugo Marconi stands in his basement workshop on Badger Island in Kittery. In 1957, Marconi was granted a U.S. patent for his plastic, seven-chambered lobster buoy design.

The multiple compartments were a failsafe design meant to keep the buoy floating in an upright position even if it sprang a leak in a chamber or two.

According to the paperwork still on file at the patent office, the device was, “To be formed entirely from molded plastic or similar material, thus to provide a highly durable, but relatively inexpensive buoy, especially adapted for manufacture by mass production methods.”

Plastic, and now foam, buoys are also less damaging to boats and propellers when accidentally run over.

Odds and ends

The Penobscot Marine Museum’s collection also boasts some unusual, lobster-gear related images.

One undated photo, possibly made in the 1960s, shows two men posing with a giant sea turtle which died after being entangled in lobster fishing gear.

The antique photo speaks directly to modern environmentalist’s fears about whale deaths due to the same thing — though no right whale death has ever been directly attributed to the Maine lobster industry, and there hasn’t been a documented right whale entanglement in lobster gear here since 2004.

Finally, a glass plate negative from the Eastern Illustrating & Publishing Company Collection collection shows an inventive, lobster-trap shaped gift shop near Lincolnville Beach. The image was made sometime around the turn of the 20th century and was used to print postcards.

The image underscores just how long lobsters, lobster gear and tourism have been entwined in Maine and — more importantly — in the outside world’s perception of the Pine Tree State.