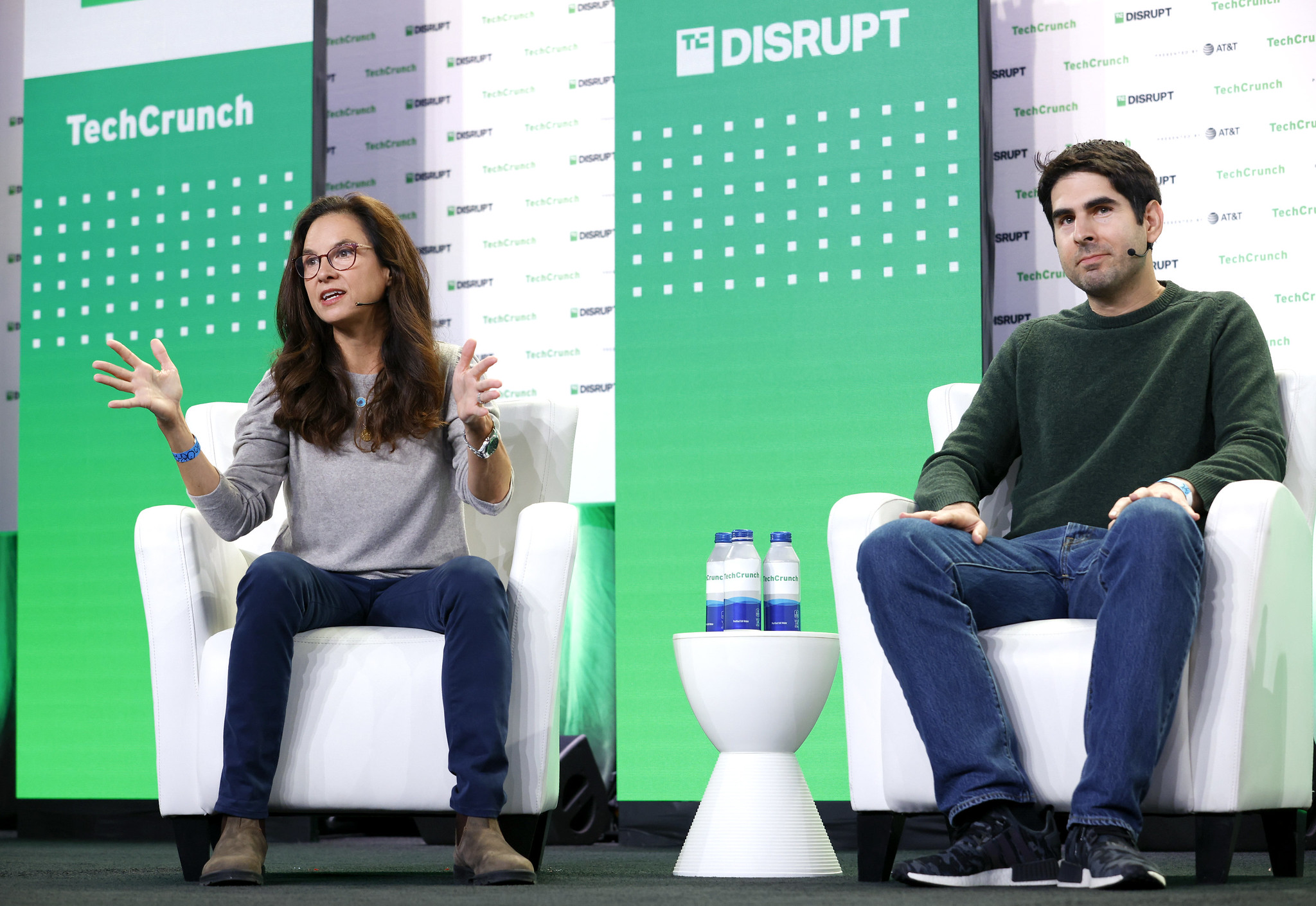

Last week at TechCrunch’s annual Disrupt event, this editor sat down with VCs from two firms that have come to look similar in ways over the last five or so years. One of those VCs was Niko Bonatsos, a managing partner at General Catalyst (GC), a 22-year-old firm that began as an early-stage venture outfit in Boston and that now manages many tens of billions of dollars across as a registered investment advisor. Bonatsos was joined onstage by Caryn Marooney, a partner at Coatue, which began life as a hedge fund in 1999 and now also invests in growth- and early-stage startups. (Coatue is managing even more billions than General Catalyst – upwards of $90 billion, per one report.)

Because of this blurring of what it means to be a venture firm, much of the talk centered on the outcome of this evolution. We wondered: does it make perfect sense that firms like Coatue and GC (and Insight Partners and Andreessen Horowitz and Sequoia Capital) now tackle nearly every stage of tech investing, or would their own investors be better off if they’d remained more specialized?

While Bonatsos called his firm and its rivals “products of the times,” it’s easy to wonder whether their products are going to remain quite as attractive in the coming years. Most problematic right now: the exit market is all but frozen. It’s also challenging to deliver outsize returns when you’ve raised the amounts that we’ve seen flow to venture firms over the last handful of years. General Catalyst, for example, closed on $4.6 billion back in February. Coatue meanwhile closed on $6.6 billion for its fifth growth-investment strategy as of April, and it’s reportedly in the market for a $500 million early-stage fund at the moment. That’s a lot of money to double or triple, not to mention grow tenfold. (Traditionally, venture firms have aimed to 10x investors’ dollars.)

In the meantime, not a single firm — about which I’m aware, anyway — has expressed plans to give investors back some of the massive amounts of capital it has raised.

I was thinking today about last week’s conversation and have some additional thoughts about what we discussed on stage (in italics). What follows are excerpts from the interview. To catch the whole conversation, you can watch it around the 1:13-minute mark in the video below.

TC: For years, we’ve seen a blurring of what a “venture” firm really means. What is the outcome when everyone is doing everything?

NB: Not everyone has earned the right to do everything. We’re talking about 10 to maybe 12 firms that [are now] capable of doing everything. In our case, we started from being an early-stage firm; early stage continues to be our core. And we learned from serving our customers – the founders – that they want to build enduring companies and they want to stay private for longer. And as a result, we felt like raising growth funds was something that could meet their demands and we did that. And over time, we decided to become a registered investment advisor as well, because it made sense [as portfolio companies] went public and [would] grow very well in the public market and we could continue to be with them [on their] journey for a longer period of time instead of exiting early on as we were doing in previous times.

CM: I feel like we’re now in this place of pretty interesting change . . .We’re all moving to meet the needs of the founders and the LPS who trust us with their money [and for whom] we need to be more creative. We all go to where the needs are and the environment is. I think the thing that stayed the same is maybe the VC vest. The Patagonia vest has been pretty standard but everything else is changing.

Marooney was joking of course. It should also be noted that the Patagonia vest has fallen out of fashion, replaced by an even more expensive vest! But she and Bonatsos were right about meeting the demands of their investors. To a large degree, their firms have merely said yes to the money that’s been handed to them to invest. Stanford Management Company CEO Robert Wallace told The Information just last week that if it could, the university would stuff even more capital into certain venture coffers as it seeks our superior returns. Stanford has its own scaling issue, explained Wallace: “As our endowment gets bigger, the amount of capacity that we receive from these very carefully controlled, very disciplined early-stage funds doesn’t go up proportionally . . .We can get more than we got 15 or 20 years ago, but it’s not enough.”

TC: LPs had record returns last year. But this year, their returns are abysmal and I do wonder if it owes in some part to the overlapping stakes they own in the same companies as you’re all converging on the same [founding teams]. Should LPs be concerned that you’re now operating in each other’s lanes?

NB: I personally don’t see how this is different than how it used to be. If you’re an LP at a top endowment today, you want to have a piece of the top 20 tech companies that get started every year that could become the Next Big Thing. [The difference is that] now, the outcomes in more recent years have been much larger than ever before. . . . What LPs have to do, as has been the case over the last decade, is to invest in different pools of capital that the VC firms give them allocation to. Historically, that was in early-stage funds; now you have options to invest in many different vehicles.

In real time, I moved on to the next question, asking whether we’d see a “right sizing” of the industry as returns shrink and exit paths grow cold. Bonatsos answered that VC remains a “very dynamic ecosystem” that, “like other species, will have to go through the natural selection cycle. It’s going to be the survival of the fittest.” But it probably made sense to linger longer on the issue of overlapping investments because I’m not sure I agree that the industry is operating the same way it has. It’s true that the exits are larger, but there is little question that many privately held companies raised too much money at valuations that the public market was never going to support because so many firms with far too much money were chasing them.

TC: In the world of startups, power shifts from founders to VCs and back again, but until very recently, it had grown founder friendly to an astonishing degree. I’m thinking of Hopin, a virtual events company that was founded in 2019. According to the Financial Times, the founder was able to cash out nearly $200 million worth of shares and still owns 40% of the company, which I find mind-blowing. What happened?

NB. Well, we were one of the investors in Hopin.

TC: Both of your firms were.

NB: For a period of time, it was the fastest-growing company of all time. It’s a very profitable business. Also COVID happened and they had the perfect product at the perfect time for the entire world. Back then Zoom was doing really, really well as a company. And it was the beginning of the crazy VC funding acceleration period that gets started in the second half of 2020. So a lot of us got intrigued because the product looked perfect. The market opportunity seemed pretty sizable, and the company was not consuming any cash. And when you have a very competitive market situation where you have a founder who receives like 10 different offers, some offers need to sweeten the deal a little bit to make it more convincing.

TC: Nothing against founders, but the people who have since been laid off from Hopin must have been seething, reading [these details]. Were any lessons learned, or will the same thing happen again because that’s just the way things work?

CM: I think that people who start companies now are no longer under that like [misperception that] everything goes up into the right. I think the generation of people that start now on both sides are going to be far more clear-eyed. I also think there was this sense of like, “Oh, I just want money with no strings attached.” . . . And that has dramatically changed [to], “Have you seen any of this before because I could use some help.”

NB: Absolutely. Market conditions have changed. If you’re raising a growth round today and you’re not one of one [type of company] or exceeding your plan dramatically, it’s probably harder because a lot of the crossover funds or late-stage investors go open up their Charles Schwab brokerage account and they can see what the terms are there and they’re better. And they can buy today; they can sell next week. With a private company, you can’t do that. At the very early stage, it’s a little bit of a function of how many funds are out there that are eager to write checks and how much capital they’ve raised, so at the seed stage, we haven’t seen much of a difference yet, especially for first checks. If you’re a seed company that raised last year or the year before, and you haven’t made enough progress to earn the right to raise a Series A, it’s a little bit harder. . .To the best of my knowledge, I haven’t seen companies decide to raise a Series A with really nasty terms. But of course we’ve seen this process take longer than before; we’ve seen some companies decide to raise a bridge round [in the hopes of getting to that A round eventually].

For what it’s worth, I suspect early founder liquidity is a much bigger and thornier issue than VCs want to let on. In fact, I talked later at Disrupt with an investor who said that he has seen a number of founders in social settings whose companies have been floundering but because they were able to walk away with millions of dollars at the outset, they aren’t exactly killing themselves trying to save those companies.

TC: The exit market is cooked right now. SPACs are out. Only 14 companies have chosen a direct listing since [Spotify used one] in 2018. What are we going to do with all these many, many, many companies that have nowhere to go right now?

NB: We’re very fortunate, especially in San Francisco, that there are so many tech companies that are doing really, really well. They have a lot of cash on their balance sheet and hopefully at some point, especially now that valuations seem to be more rationalized, they will need to innovate through some M&A. In our industry, especially for the large firms like ours, we want to see some smaller exits, but it’s about the enduring companies that really can go the distance and produce a 100x return and pay for the whole vintage or the whole portfolio. So it’s an interesting time, what’s going on right now in the exit landscape. With the terms rationalizing, I would assume we’ll see more M&A.

Naturally, there will never be enough acquisitions to save most of the companies that have received funding in recent years, but to Bonatsos’s point, VCs are betting that some of these exits will be big enough to keep institutional investors as keen on VC as they’ve grown. We’ll see over the next couple of years if this gamble plays out the way they expect.

Top VCs have expanded into broader asset managers; is the model sustainable? by Connie Loizos originally published on TechCrunch