The emotion as chairwoman Rena Lee announced that a UN high seas treaty had finally been agreed reflected her exhaustion, relief and the sheer human endeavour that multilateralism entails.

In a divided world, getting 193 nations to consensus on anything is hard.

But reaching a brand new politically-sensitive pact covering nearly two thirds of the planet’s oceans that don’t actually belong to anyone is another thing entirely.

That’s why UN member states have been struggling for the best part of two decades to find a way of protecting the high seas.

On paper, they have done just that, and not a moment too soon.

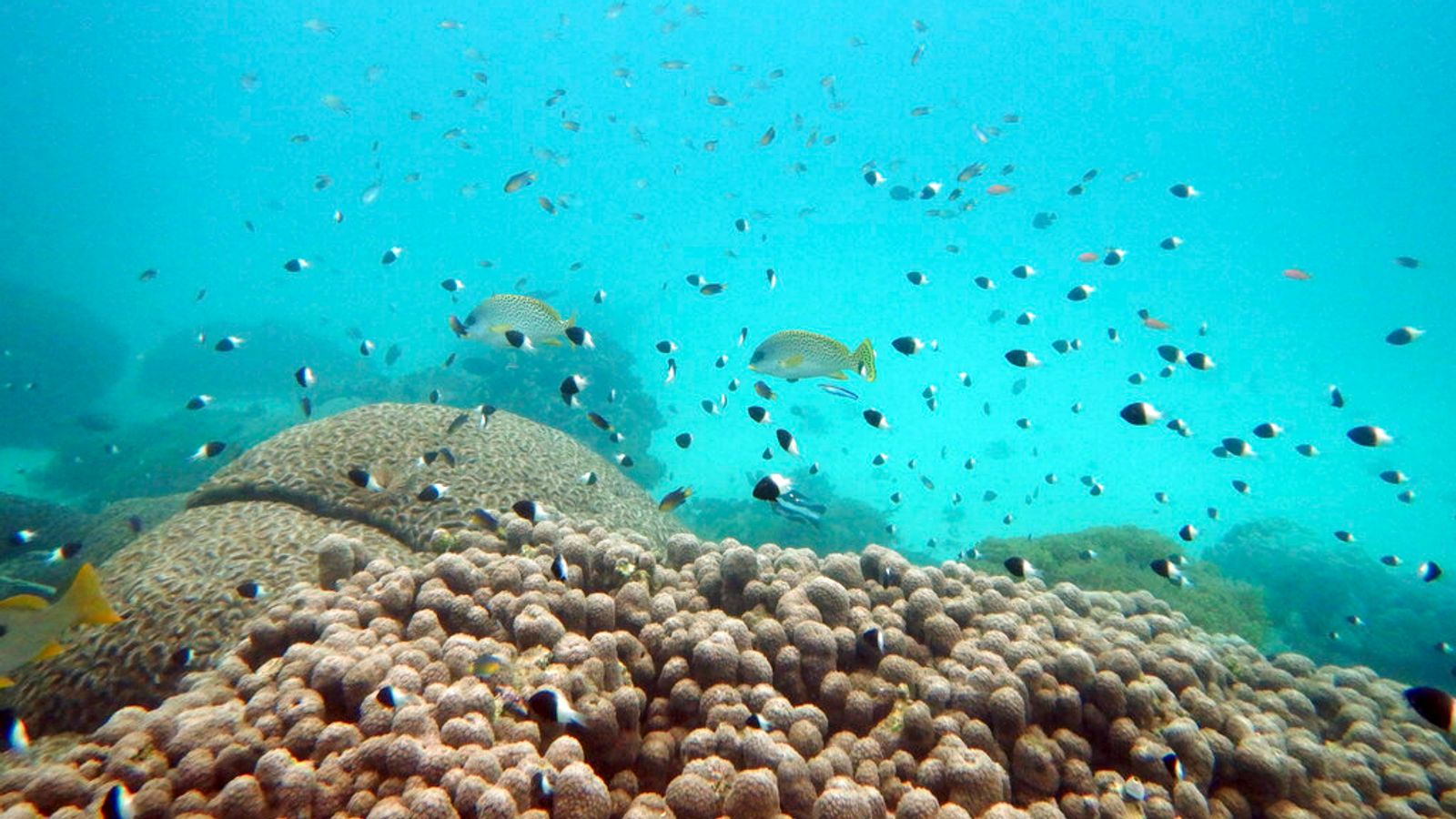

Our oceans and the biodiversity within them sustain life on Earth.

They produce nearly half of the planet’s oxygen and absorb a quarter of its carbon dioxide and the excess heat that it generates.

But they are under severe threat from pollution, overfishing and global warming.

Please use Chrome browser for a more accessible video player

As US climate envoy John Kerry put it recently: “The ocean is life itself.

“That life is being threatened because of the very reckless and careless activities of human beings without thinking about the impact and without taking into account that it is a living organism, a living system. And given the wrong inputs that system can be killed.”

Actor and activist Jane Fonda put it rather less delicately: “We’re pooping in our kennel. We are supposed to be so smart. We are destroying things we don’t even understand.”

Read more:

UN high seas treaty finally agreed to protect vast swathes of planet’s oceans

Sharks in decline due to climate change, but tuna population is ‘on path to recovery’

UN countries agree to create ‘historic’ treaty to fight plastic pollution

The treaty, in a nutshell, will provide a legal framework for establishing vast marine protected areas (MPAs).

This means that all activities that go on in the high seas will be subject to environmental impact assessments, with member states held accountable for their actions.

The treaty itself focuses on four main areas, according to charity WWF: marine genetic resources, area-based management tools, environmental impact assessments, and the transfer of marine technology and building of capacity.

This could mean restrictions on how much fishing can take place and on activities such as deep-seabed mining and deep-sea carbon capture and storage.

Before now, efforts to protect marine species including dolphins and whales — and human communities that rely on fishing or tourism related to marine life — have been hampered by a confusing patchwork of laws.

It is hoped that the obligation on developed states to share knowledge and technologies, and to build capacity, will result in, particularly developing nations, participating more in the conservation of the high seas.

Jessica Battle, oceans governance expert at the Worldwide Fund for Nature, said: “This treaty will help to knit together the different regional treaties to be able to address threats and concerns.”

So the UN high seas treaty really is a milestone in a journey littered with failures and false starts.

But there is still a long way to go.

The deal establishes the legal framework for the creation of vast marine protected areas which will help to control fishing, deep-sea mining and shipping, as well as agreeing on the equitable distribution of newly discovered resources.

This will be tremendously complicated in practice, involving overlapping and competing industries and organisations finding a way to work in harmony in what has essentially been a lawless place.

Subscribe to ClimateCast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or Speaker

Experts have already warned that the treaty must be rapidly adopted, ratified and implemented in order to make a genuine impact.

And, they warn, it is not yet clear how any of this will be enforced.

As delegates travel home from New York, they will be aware of all of this, and that the hard work has really only just begun.

But on this occasion, they will also know that they have been a part of shaping an historic agreement, one that shows the power of multilateralism and how it can help us fight the climate crisis.