The BDN Editorial Board operates independently from the newsroom, and does not set policies or contribute to reporting or editing articles elsewhere in the newspaper or on bangordailynews.com.

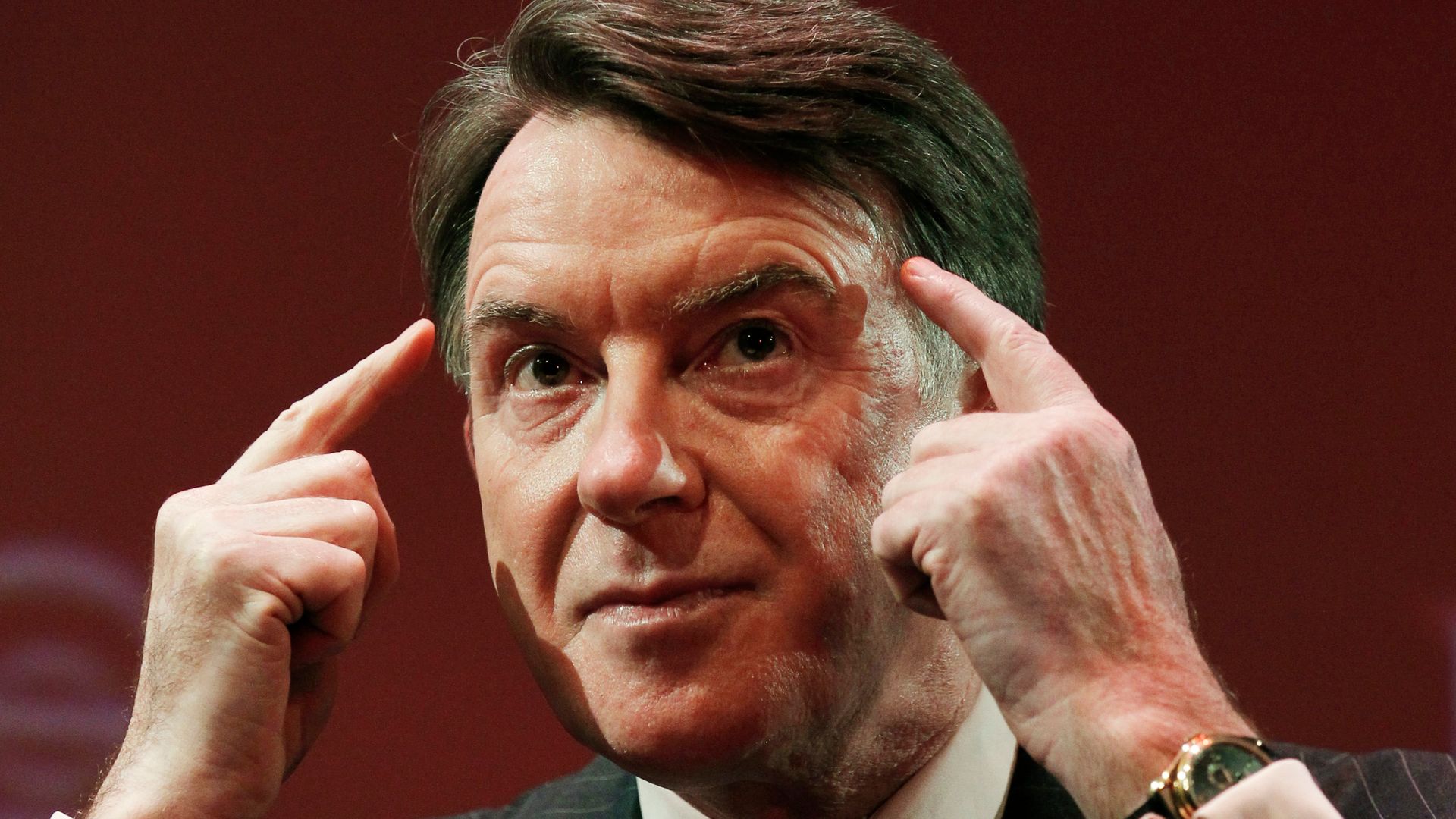

If anyone needs another warning sign about the precarious status of Maine’s judicial system, and there have been many, look no further than the recent reporting about Eliot Cutler.

The former independent gubernatorial candidate turned criminal defendant has reached a plea deal, according to prosecutors, after being arrested on child pornography charges last year. Robert Granger, the district attorney for Hancock and Washington counties, has indicated that the deal materialized in part because of the significant case backlog — a persistent and alarming reality both in his prosecutorial district and across the state. This backlog is 65 percent higher than it was before the Covid-19 pandemic.

“Plea agreements are essential if we are serious about trying to bring the criminal dockets under control,” Granger told BDN reporter Bill Trotter earlier this month. “It is not uncommon for cases to languish on the criminal docket for three or more years given the case backlog.”

Given that Cutler is also 76 years old, Granger said that “we had to also consider the real possibility that he might not ever see the inside of a courtroom during his lifetime.” The plea has yet to be accepted by the court. As of mid April, Cutler is scheduled to appear in court on May 4 to enter a plea.

This is a high-profile example of what has been a slow-moving judicial emergency. When prosecutors are turning to a deal, despite a seemingly strong case, in order to ensure a prominent defender sees some measure of accountability while they are still alive, there is clearly something wrong in a system that is constitutionally obligated to provide access to a fair and speedy trial.

This status quo is unacceptable both for victims seeking justice and for defendants who are presumed innocent until being found guilty.

While a wealthy defendant like Cutler may be able to weather an extended process like this, having been released the same day as his arrest on $50,000 cash bail, this protracted backlog can have a much heavier impact on less powerful members of our society. Defendants without Cutler’s level of resources — which is most other defendants — can languish in jail for long periods of time as they wait for their time in court.

It is sadly no wonder that Maine’s top judicial official, Chief Justice Valerie Stanfill of the Maine Supreme Judicial Court, has been raising the alarm about the state of the state’s judiciary. After a recent address to state lawmakers in March, Stanfill described Maine’s judicial branch as “frail” and previously said the court system is “failing” last fall. Despite concluding her March 23 speech with notes of hope, we’re left feeling that the alarm bells are warranted, and should inspire action.

“To be clear, it’s not the people in the judicial branch who are failing,” she told the Maine Monitor in November. “We just don’t have the ability to serve the people of Maine the way they deserve.”

In her recent address to the Legislature, Stanfill asked for funding to support additional judicial branch positions, including several new judges. Gov. Janet Mills’ office has signaled her support for this funding for new judges, clerks and marshals. Her initial biennial budget proposal also included funding for more public defenders, but that funding was not included in the party-line $9.8 billion “current services” budget passed by Democrats at the end of March. The funding for these various positions must survive the additional budget discussions as they continue this spring — and not just because it could impact a potential legal settlement with the ACLU over the sorry state of Maine’s indigent legal services.

Yes, Maine needs to hire and retain more judges, other court officers, and lawyers for Maine’s financially disadvantaged defendants. In addition, legislative and court officials should pursue ways to help unclog the system that involve prosecuting fewer non-violent crimes (something that the decriminalization of certain types of personal drug use in small amounts could help achieve, by the way).

State leaders must also recognize that the judicial system isn’t operating in a vacuum and that the failures and shortcomings in other areas and institutions impact the court backlog as well. In the long term, making more investments in mental health and substance use supports, as well as stable housing and economic opportunity, can help break devastating cycles that are impacting Maine families and the court system alike.

It was not one single issue that has brought Maine’s judiciary to this precarious place, and it will not be one single policy that rights the ship. Many steps, and sustained investment in different areas, will be needed to strengthen this frail but vital system.