It is one of the great set-piece moments in the US industrial calendar.

At the start of pay negotiations, which take place every four years ahead of the expiry of existing contracts in September, the leaders of the big three US carmakers traditionally shake hands in front of the cameras with the leader of the United Auto Workers (UAW) union.

The tradition goes back almost a century: Wayne State University in Detroit, America’s car-making capital, has unearthed photographs dating back to the 1930s showing the UAW leaders of the time shaking hands with a leader from Ford, Chrysler or General Motors.

This was the precursor to another established tradition under which the UAW would select a lead company with which to negotiate. Then, once a deal had been struck, the other carmakers would follow the first company’s lead in a process known as ‘pattern bargaining’.

So it was a seismic moment when, in July this year, the UAW’s new president, Shawn Fain, declined to take part in the handshake.

Instead, he held what were described as a “member’s handshake”, during which he met with workers at the big three (Chrysler is now owned by Stellantis, also the parent company of European carmakers Peugeot and Fiat) as they came off their shifts.

It was intended to lay down a marker to the carmakers that this was a very different UAW leadership.

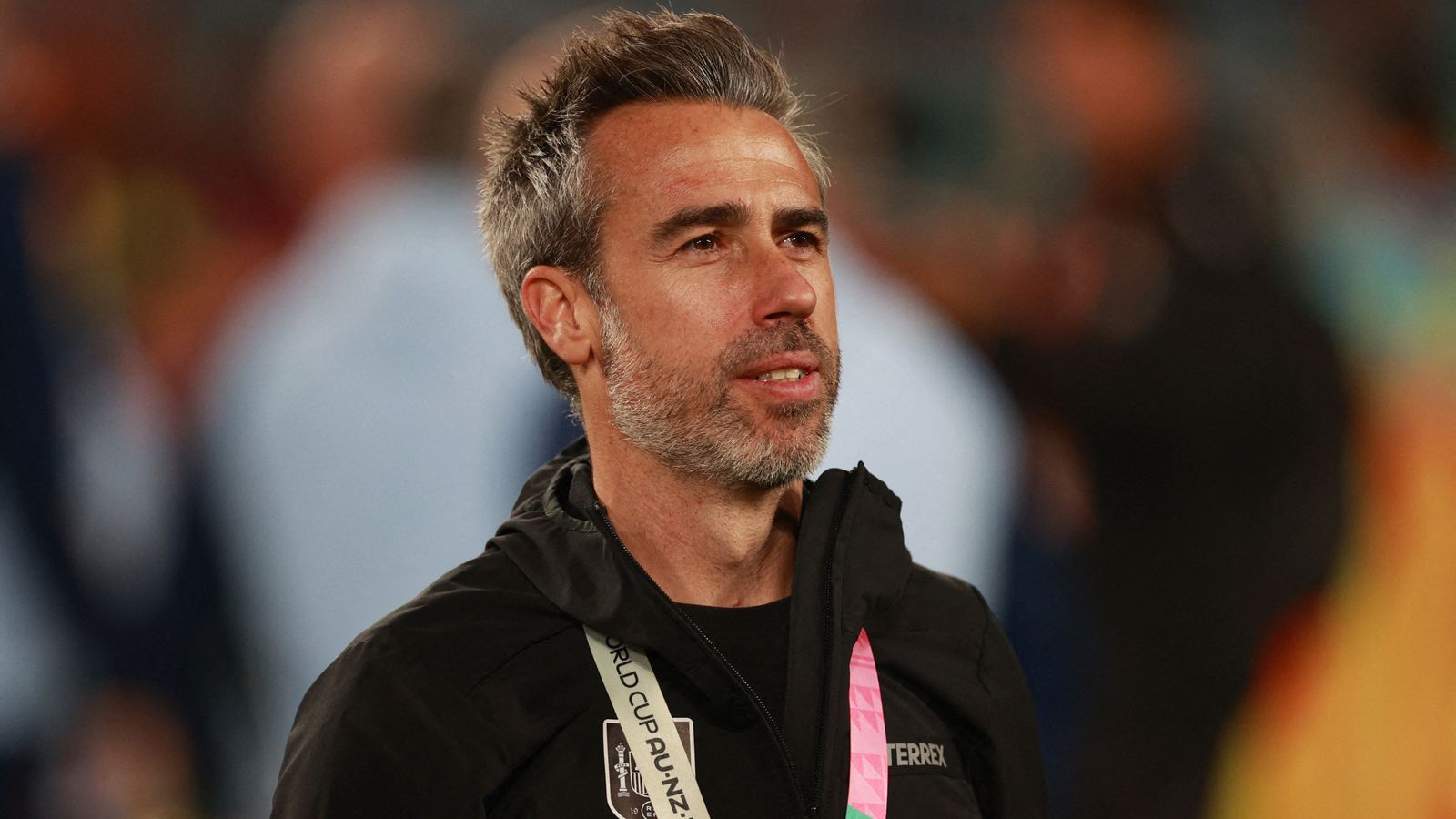

Mr Fain, 54, was narrowly elected president of the UAW in March this year on a platform of promising a tougher approach to pay negotiations.

His victory, over the existing president Ray Curry, was historic in that it was the first in which the president, and other leading officials, were chosen by a direct ballot of members rather than in a proverbial smoke-filled room in which delegates chose the leadership.

Mr Fain, in winning, toppled a faction of the union that had controlled it for decades.

On being elected, Mr Fain – who began his career as an electrician with Chrysler – immediately served notice on the carmakers that he did not intend this to be business as usual, declaring: “We’re here to come together to ready ourselves for the war against our one and only true enemy: multibillion corporations and employers that refuse to give our members their fair share. It’s a new day in the UAW.”

If that didn’t make the carmakers sit up and take note, Mr Fain’s refusal to take part in the traditional handshake did, as he told the union’s 389,000 members on his social media feed: “I’m not shaking hands with any CEOs until they do right by our members, and we fix the broken status quo with the big three. The members have to come first.”

For good measure, he very publicly threw a Stellantis pay offer in a bin.

Mr Fain’s approach is making waves on Wall Street.

There are real concerns that Mr Fain – who carries around with him one of his grandfather’s payslips from Chrysler in 1940 – will bring out his members at all three carmakers if a deal is not reached by the time the existing contracts expire on 14 September. Such action would be unprecedented.

Read more business news:

Bank of England’s ‘regrettable mistakes fuelled inflation’

B&M to snap up 51 Wilko stores

Birmingham City Council effectively declares bankruptcy

Members at the three have voted for strike action in the event of negotiations breaking down, by an average of 97%.

Strikes would cause immense disruption at a time when the carmakers are having to invest billions in electrification while trying to cut their costs in response to inflation.

Yet, with Wall Street putting the odds of strike action at the big three as better than events, the two sides look set for collision.

Be the first to get Breaking News

Install the Sky News app for free

The UAW is not only seeking to restore past benefits lost in previous pay negotiations, but also to cut the working week to 32 hours.

It is also seeking a significant pay rise, the extent of which it has not made public, but which has been reported by the Wall Street Journal as 46%.

That would severely hobble the big three’s competitiveness against foreign rivals, from Germany and Japan – which tend to have less union representation in their workforces, as well as the likes of non-unionised Tesla.

Some 150,000 of the UAW’s members work for Ford, GM and Stellantis but strikes at all three would be huge because the union has traditionally singled out an individual carmaker for strike action rather than attacking several targets at once. It would also be a risk.

The union has a strike fund of $900m (£716m) – half of which would be eaten by a six-week stoppage in which striking members at the big three were each paid $500 (£398) a week.

That is why it has been suggested that Mr Fain may adopt another tactic, bringing out its members at the car parts makers instead, in time depriving the big three of components and forcing them to temporarily close plants while still having to pay workers.

That, though, would also be a risk for the UAW, as it is not nearly as well represented among the parts makers.

Mr Fain’s election is not just rattling Wall Street – but also in Washington. Mr Fain has refused to say whether the union will endorse and provide support to Joe Biden as he seeks re-election to the White House next year.

He told the Boston Globe at the weekend: “I’ve tried to be clear with people: The days of us just freely giving endorsements are over. Our endorsements have to be earned.”

Those comments speak to his unease that, as the Biden administration offers huge subsidies to businesses involved in the transition to net zero, it is not doing so with sufficient protection for carmakers.

He was particularly unhappy at a $9.2bn (£7.3bn) loan awarded by the Biden administration in June to a joint venture between Ford and a South Korean company to build three battery factories in Kentucky and Tennessee.

Mr Fain felt the loan should have come with strings attached on wages and working conditions.

He told the Globe: “We support a green economy. We have to have clean air, clean water, but this transition has to be a just transition. Workers can’t be left behind.”

Mr Fain’s election must also be seen in the context of changing circumstances in America’s unions.

The powerful Teamsters union, like the UAW, has also jettisoned the ruling faction that has run it for decades in favour of more radical leadership. Its aggressive stance is credited with having won it a pay deal with United Parcel Services reckoned to be the most generous in the company’s history.

Part-time workers at UPS were awarded a reported 50% pay rise while other concessions agreed by the company included a promise to instal air conditioning in all of its trucks.

Mr Fain is clearly optimistic that he has the wind to his back and can secure similar wins for his members. If he succeeds, other union leaders will be taking note.

It is why the month of September promises to be a momentous one for US industry.