The relationship between the state and the Wabanaki tribes in Maine is strained much of the time, said Penobscot Tribal Ambassador Maulian Dana Bryant. But she hopes the resounding voter support in the passage of Question 6 in the recent election sends the message that Mainers care about tribal rights.

“As we go into the new legislative session we will have a bill by Rachel Talbot Ross addressing sovereignty and this is a really great message to send,” she said “I think that it does us all a lot of good to have as much transparency and clarity around these things. We are optimistic that this continues to move the needle.”

Nearly three-fourths of Maine voters supported tribal rights on Nov. 7 and the passage of question six means that for the first time in nearly 150 years the state’s constitution, including the state’s treaty obligations to the Wabanaki people, can be printed in full. The Wabanaki people include the Penobscot and Passamaquoddy nations as well as the Maliseet and Mi’kmaq tribes.

An overwhelming majority of voters made it clear to the state that making the Wabanaki people’s treaty history visible to everyone was important and that they did not support an 1876 constitutional amendment barring the printing of Article X that details the Wabanaki treaty history.

Several state leaders, including Attorney General Aaron Frey and Maine Secretary of State Shenna Bellows supported amending the constitution to allow its printing in full. Gov. Janet Mills opposed it, keeping in line with her rejection of other legislative measures aimed at freeing the Wabanaki people from state control.

Democratic House Speaker Talbot Ross, a tribal sovereignty advocate, sponsored the 2023 bipartisan sovereignty bill that Gov. Mills vetoed in June.

Most Wabanaki children grew up never hearing about the work, lives and diplomacy of their ancestors in classrooms. Only elders’ stories kept the Wabanaki treaty history alive for native children, said Zeke Crofton-Macdonald, Houlton Band of Maliseet Indians tribal ambassador.

It was something we heard from our elders for a very long time, he said.

“It feels gratifying and proud to finally have this changed and finally have this acknowledged,” said Crofton-Macdonald. “I do have hope this will open some doors. With such overwhelming support the people have spoken and they are willing to embrace change. I hope the momentum will continue.”

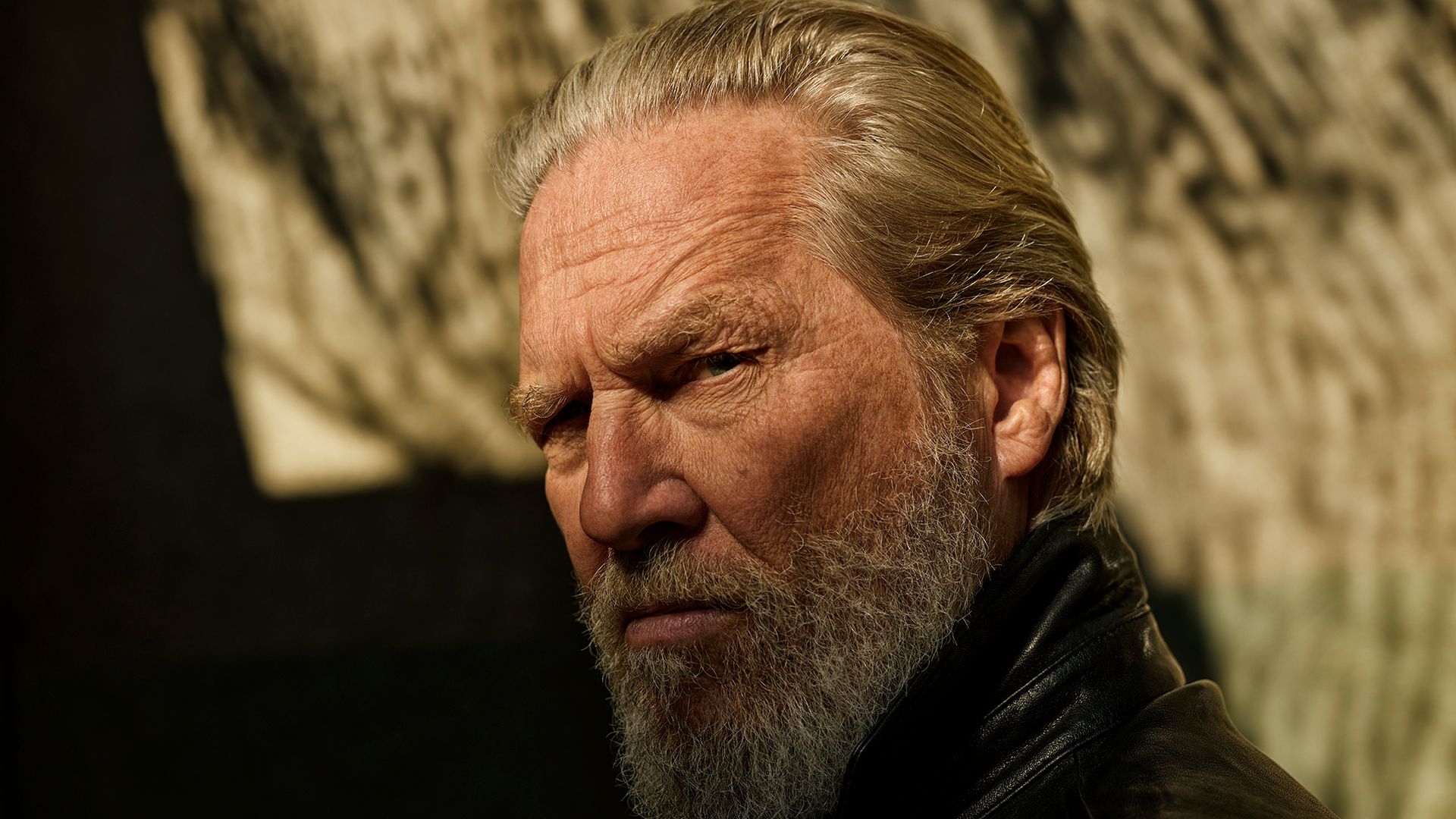

Crofton-Macdonald said retired state representative Henry Bear, who represented the Houlton Band of Maliseet Indians in the state house, put a bill forward and put this issue on state government radar in 2015.

“It wasn’t successful back then but that’s when it began as a bill LD78,” he said. “In my opinion this question is relevant to every single person in Maine and steps should be taken to get it into the schools.”

According to Bear, he discovered that Article X was missing from the printed constitution when he was trying to figure things out as a new legislator.

“I noticed that there were secret sections not printed,” he said on Friday.

Bear, an attorney, who heads the Aroostook Treaty Education Center, said that Article 10 requires the State to comply with treaty obligations contained in shared treaties, including the Paris Treaty of 1783, which formally ended the American Revolutionary War.

“That treaty specifically required the United States comply with all treaties, including the treaties of 1725, 1726, 1749 and 1760 regarding non-interference with tribal hunting, fishing and fowling rights and the tribes unextinguished ownership of aboriginal title-held homelands,” Bear said.

As Bear explained, the treaties spell out the Wabanaki rights to hunt and fish on tribal lands recognized in the treaties.

Bryant said that Article X highlights the fact that Wabanaki people have been stewards of the land they call Maine for thousands of years.

“We feel really honored for our ancestors. Our people were included in the 1820 documents and it is important to include them in the printed copies of the constitution to honor them for their diplomacy and their work and their legacy,” she said. “It also shows that original social contract between the State of Maine and the tribes.”